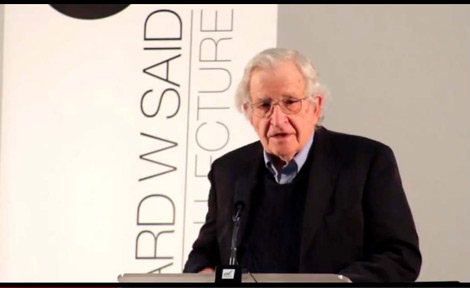

Violence and Dignity: Reflections on the Middle East

Noam Chomsky

2013 Edward Said Lecture, Friends House, London, March 18, 2013

Swedish novelist Henning Mankell tells of an experience in Mozambique at the peak of the hideous atrocities of the apartheid era, when he saw a thin man walking towards him in ragged clothes. “In his deep misery,” Mankell relates, the wretched survivor had “painted shoes on his feet. In a way, to defend his dignity when everything was lost, he had found the colors from the earth and he had painted shoes on his feet.”

Such scenes will evoke poignant memories among those who have witnessed cruelty and degradation, and also the steady resistance of the “samidin” — those who endure, to borrow the evocative term of Raja Shehadeh’s in his remarkable book on Palestinians under occupation, 20 years ago.

Like many of you, and in fact much less than many of you, I have witnessed such scenes throughout the world over many years. Once again, last October, when I was able to visit Gaza for the first time, after several earlier attempts failed. Greeting me on my return home were the reports on the latest outburst of shocking crimes, the November Israeli onslaught, supported by the US and tolerated politely by Europe.

One of the first reports I received was a photograph by a young Gaza journalist with whom I had spent some time in Gaza. It showed a doctor in a hospital ward holding the hideously charred corpse of a murdered infant. The doctor is the director and head of surgery at the Khan Yunis hospital, where a few days I earlier I had heard his passionate appeal for drugs and surgical equipment so that patients would not have to writhe in agony while awaiting simple surgery that cannot be performed for lack of facilities.

As the November attack exploded in full fury, the United Nations released its weekly review of the permanent humanitarian crisis in Gaza: it reported that 40% of essential drugs and 55% of essential consumables were out of stock, a consequence of the Israeli blockade and western complicity, and the unwillingness of the new Egyptian government to offend the masters. The border, it appears, remains largely under the control of Mubarak’s dreaded Mukhabarat, which was closely linked to the CIA and the Israeli Mossad according to credible reports. Just last week I received another article by the same Gaza journalist describing the terrible impact of the Morsi government’s latest assault against the people of Gaza. It has devised a new way to block the tunnels that are a lifeline for people imprisoned under harsh siege and constant attack: flooding them with filthy sewage.

The same day’s news brought a report by the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem on a new device adopted by the Israeli army to overcome the ingenuity of the Samidin in coping with tear gas and other population control methods: spraying protestors and homes with powerful jets of raw sewage as punishment for the weekly non-violent protests against Israel’s illegal Separation Wall — in reality an Annexation Wall.

More evidence that great minds have similar thoughts, in this case combining criminal repression with useful humiliation.

The tragedy of Gaza traces back to 1948, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinians fled in terror or were forcibly expelled to Gaza by conquering Israeli forces, who continued to truck them over the border long after the official cease-fire, for at least four years. Recent Israeli scholarship, notably the important work of Avi Raz, reveals that the government’s goal was to drive the refugees into the Sinai, and if feasible also the rest of the population of Palestine. In the words of Golda Meir, later Labor Prime Minister, the intention was to keep the Gaza Strip while “getting rid of its Arabs.” These long-standing goals might be a factor contributing to Egypt’s reluctance to open the border to free passage of people and goods barred by the cruel western-backed Israeli siege.

Getting rid of the Arabs of Gaza was only one facet of much broader goals. During the 1948 expulsions, Israeli government Arabists predicted that the refugees would either assimilate elsewhere or “would be crushed” and “die,” while “most of them would turn into human dust and the waste of society, and join the most impoverished classes in the Arab countries.” Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s view for the “Arabs of the Land of Israel” who remained after the expulsion of 1948 was that they “have only one function left to them — to run away.” Though vigorously denied for many years, the causes of the refugee flight are no longer seriously in question. Few would question the conclusions of the most prominent Israeli historian of the topic, Benny Morris. In his words, “Above all, let me reiterate, the refugee problem was caused by attacks by Jewish forces on Arab villages and towns and by the inhabitants’ fear of such attacks, compounded by expulsions, atrocities, and rumors of atrocities — and by the crucial Israeli cabinet decision in June 1948 to bar a refugee return,” leaving the Palestinians “crushed, with some 700,000 driven into exile and another 150,000 left under Israeli rule.” Morris is critical of Israeli atrocities, in part because they were too limited. Ben-Gurion’s great error, Morris observes, perhaps a “fatal mistake,” was not to have “cleansed the whole country — the whole Land of Israel, as far as the Jordan River.” Recently declassified cabinet records indicate that Ben-Gurion may have agreed that it was a serious error.

From the earliest days, Arabs were regarded as an alien implant in the Land of Israel, who would be just as happy anywhere else in Arab domains. As the Balfour Declaration was released, Chaim Weizmann, the first President of Israel and the most respected Zionist figure, remarked that the British had informed him that in Palestine “there are a few hundred thousand Negroes, but that is a matter of no significance.” Weizmann had in turn informed Lord Balfour that “the issue known as the Arab problem in Palestine will be of merely local character and, in effect, anyone cognizant of the situation does not consider it a highly significant factor.” Hence displacement of the inhabitants by Jewish settlement raises no moral issue. A later Israeli president, Haim Herzog, also a Labor Dove, articulated the basic guidelines in 1972: “I do not deny the Palestinians any place or stand or opinion on every matter. But certainly I am not prepared to consider them as partners in any respect in a land that has been consecrated in the hands of our nation for thousands of years. For the Jews of this land there cannot be any partner.”

Lord Balfour himself, a devoted Christian Zionist, expressed similar views. These were a common element of elite Christian Zionism, which long predates Jewish Zionism. It has included leading figures in the US as well, immersed in the Holy Book with its lessons that the Land of Israel was promised to the Jews by the Lord and that others are interlopers. That is why, for example, one of FDR’s advisers and an important cabinet member described the Jewish return to Palestine as “the most remarkable historical event in history.” In the United States traditional elite Christian Zionism is now buttressed by an enormous right-wing Christian movement, passionately pro-Israel and deeply anti-Semitic, forming much of the current base of the modern Republican Party.

Christian Zionism is an important factor, often ignored, in shaping policy towards Israel-Palestine, from early years. There are others. It is noteworthy, for example, that the strongest support for Israel in the international arena comes from the US, Canada, and Australia, the so-called Anglosphere, settler-colonial societies based on extermination or expulsion of indigenous populations in favor of a higher race, and where such behavior is considered natural and praiseworthy. The crucial factors, since 1967, are strategic and economic, and still prevail. But others should not be ignored.

Returning to Gaza, after Israel’s 1967 conquests, its torture took new forms. Merely to mention one of innumerable examples, immediately before the outbreak of the Intifada in Gaza in December 1987, a Palestinian girl was shot and killed in a schoolyard by a resident of a nearby Jewish settlement. Like other “unpeople,” to borrow Orwell’s phrase, her name — Intissar al-Atar — is unknown in the civilized world, her fate as well. The murderer was one of the several thousand Israelis settlers brought to Gaza in violation of international law and protected by a huge army presence, taking over much of the land and scarce water of the Strip and living “lavishly in twenty-two settlements in the midst of 1.4 million destitute Palestinians,” as Raz describes the crime. The murderer of the schoolgirl, Shimon Yifrah, was arrested, but quickly released on bail when the Court determined that “the offense is not severe enough” to warrant detention. The judge commented that Yifrah only intended to shock the girl by firing his gun at her in a schoolyard, not to kill her, so “this is not a case of a criminal person who has to be punished, deterred, and taught a lesson by imprisoning him.” Yifrah was given a 7-month suspended sentence, while settlers in the courtroom broke out in song and dance. And the usual silence reigned. After all, it is routine.

And so it is. As Yifrah was freed, the Israeli press reported that an army patrol fired into the yard of a school for young boys in one of the miserable refugee camps, wounding five children, allegedly intending only “to shock them.” There were no charges, and the event again attracted no attention. It was just another episode in the program of “illiteracy as punishment,” the Israeli press reported, including the closing of schools, use of gas bombs, beating of students with rifle butts, barring of medical aid for victims; and beyond the schools a reign of more severe brutality, becoming even more savage during the Intifada, under the orders of Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin, an admired dove, who informed a Peace Now delegation at the peak of the brutality that he was pleased with the meaningless US-PLO dialogue that had just been initiated, “low-level discussions” that avoid any serious issue and grant Israel “at least a year" to resolve the problems by force. “The inhabitants of the territories are subject to harsh military and economic pressure,” Rabin explained, and “In the end, they will be broken,” abandoning their hopes for a life of dignity.

Shortly afterwards, Gaza was placed under closure, breaking any connection to the rest of Palestine. That was extended in the framework of the Oslo accords of 1993, which declared that Gaza and the West Bank are an indivisible territorial unity. It remains US-Israeli policy to the present. Separation of the two regions in violation of the pledges at Oslo is a crucial policy goal: it guarantees that any limited autonomy that might be achieved in the West Bank will have no access to the outside world apart from Jordan, and that is being barred by the systematic takeover of the Jordan Valley. Its Palestinian population of 300,000 before 1967 has been reduced steadily to less than 60,000. By now more than three-fourths of the Valley is free of Palestinians in a program that the Israeli press accurately calls “tihur babiq’a,” cleansing in the Valley. Regular expulsions continue, with extreme cruelty.

We will soon be commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Oslo accords, which were hailed at the time as a historic breakthrough on the path towards resolution of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Not hailed universally of course, certainly not by prominent Palestinian figures, among them Raja Shehadah, Palestine’s leading legal specialist, who had been trying in vain for years to block Israel’s violations of international law in the territories and who recognized that the accords were a surrender in the interests of the Tunis-based PLO, which was being marginalized within the territories but now restored to power. Another was Edward Said, who saw exactly what was happening and condemned the capitulation at once. Historian Rashid Khalidi, an adviser to Palestinian negotiators, describes the Oslo accords as an “infernal trap.” Still another was Haidar abdul-Shafi, probably the most respected Palestinian within the territories. He headed the Palestinian delegation at the US-run Madrid negotiations. Refusing to capitulate to US-Israel demands, he insisted that any agreement must bar illegal Israeli settlement in the territories. The issue was ignored at Oslo, and Abdul-Shafi refused to attend the signing ceremony on the White House lawn, a “day of awe” as it was described in the US press.

There were many illusions about Oslo, but no basis for them. To understand what was taking place it was only necessary to read the brief Declaration of Principles, which was quite explicit about satisfying Israel’s demands, while completely silent on Palestinian national rights. Article I states that the end result of the process — the end result — is to be “a permanent settlement based on Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338.” That tells the whole story. These resolutions say nothing at all about Palestinian rights, apart from reference to a “just settlement of the refugee problem,” left vague. UN resolutions referring to Palestinian national rights were ignored. If the culmination of the “peace process” would be as clearly articulated in the Declaration of Principles, then Palestinians could kiss goodbye to their hopes for some limited degree of national rights in the former Palestine.

All of this was suppressed in mainstream western commentary, and will probably be ignored at the 20th commemoration, though not in Norway at least, where there is some recognition of what a severe blow the Oslo Accords were to Palestinian aspirations.

The assault on the people of Gaza escalated sharply in January 2006, when Palestinians committed a major crime: in the first free election in the Arab world, they voted “the wrong way.” Such insubordination conflicts sharply with the really existing passion for democracy that is regularly proclaimed by western leaders and the political class. At once, the US and Israel, with Europe following obediently, instituted harsh measures to punish the miscreants. Punishment became even more severe a year later, when Gazans committed an even worse crime. After the elections, Washington had turned to standard operating procedure when criminal populations vote improperly: preparing a military coup, to be led by Fatah strongman Muhammed Dahlan. The elected government preempted the coup, an event denounced in the West as Hamas’s violent takeover of Gaza, the context suppressed. It is bad enough to vote the wrong way in a free election, but preventing a US-run military coup to overthrow the government is a truly unspeakable crime. Accordingly, the siege and other punishments were sharply increased in retaliation. We then move on to Cast Lead and other atrocities. I won’t review the shocking story, which westerners should know by heart given their critical role throughout.

Throughout these years Gaza has been a showcase for violence of every imaginable kind. The record includes such sadistic and carefully planned atrocities as Operation Cast Lead — “infanticide,” as it was called by the remarkable Norwegian physician Mads Gilbert who worked tirelessly at Gaza’s al-Shifa hospital with his dedicated Palestinian and Norwegian colleagues right through the criminal assault — a fair term, considering the hundreds of children massacred. And from there the violence ranges through just about every kind of cruelty that humans have used their higher mental faculties to devise, up to the pain of exile that Edward Said wrote about so eloquently. This is particularly stark in Gaza, where older people can still look across the border towards the homes a few miles away from which they were driven — or could if they were able to approach the border without being killed. One form of punishment has been to close off the Gaza side of the border area, including almost half the arable land, according to the leading academic scholar of Gaza, Harvard’s Sara Roy.

While a showcase for the human capacity for violence, Gaza is also an inspiring exemplar of the demand for dignity. The first phrase one hears in Gaza when asking about personal aspirations is for a life of dignity. The distinguished human rights lawyer Raji Sourani writes from his Gaza home that “What has to be kept in mind is that the occupation and the absolute closure is an ongoing attack on the human dignity of the people in Gaza in particular and all Palestinians generally. It is systematic degradation, humiliation, isolation and fragmentation of the Palestinian people.” While the bombs were once again raining down on defenseless civilians in Gaza last

November he repeated that “We demand justice and accountability. We dream of a normal life, in freedom and dignity.”

Many others perceive much the same reality. In the Lancet, a visiting Stanford physician, appalled by what he witnessed, described Gaza as “something of a laboratory for observing an absence of dignity,” a condition that has “devastating” effects on physical, mental, and social wellbeing. “The constant surveillance from the sky, collective punishment through blockade and isolation, the intrusion into homes and communications, and restrictions on those trying to travel, or marry, or work make it difficult to live a dignified life in Gaza.”

A young woman professional who managed to escape from Gaza to Canada, Ghada Ageel, writes about her 87-year old grandmother, still trapped in the Gaza prison: before her expulsion, “she owned a house, farms, and land and she enjoyed honor, dignity and hope.” And amazingly, like Palestinians quite generally, she hasn’t given up hope. Ageel continues: “When I saw my grandmother in November 2012 she was unusually happy. Surprised by her high spirits, I asked for an explanation. She looked me in the eye and, to my surprise, said that she was no longer worried about” her native village and the life of dignity that she has lost, for her irrevocably. When I see you, her grandmother said, I know that our native village — long ago destroyed — “is in your heart, and I also know that you are not alone in your journey. Don’t be discouraged. We are getting there."

The call for dignity resounds through the Arab Spring, which, despite all its uncertain outcomes, is doubtless a development of historic significance. The prominent commentator Rami Khouri writes that “the process at hand now in Tunisia and Egypt will continue to ripple throughout the entire Arab world, as ordinary citizens realize that they must seize and protect their birthrights of freedom and dignity.” The uprising was sparked by the self-immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi in reaction to his humiliating and degrading treatment. “Mohammed did what he did for the sake of his dignity,” his mother recounts. On the anniversary of his suicide a cart statue was unveiled in his honor in the town where he carried out the action that triggered the uprising. The ceremony was attended by Tunisia’s first elected president, who thanked him and those inspired by “for bringing dignity to the entire Tunisian people."

In the oil dictatorships the uprisings have been suppressed, often by violence, much to the relief of western powers. But not entirely. In Kuwait, while protestors fled from the riot police, a Kuwaiti political scientist commented that “People want dignity and political participation and equality before the law,” not a revolution. Not the Kuwaiti citizens at least. The great majority who do the work might have other ideas in mind.

Such driving sentiments of oppressed people extend far beyond the Arab spring. We have just passed the centenary of the great textile strike of immigrant workers in Lawrence Massachusetts, led by the Wobblies, who played a leading role in the labor movement until it was crushed a few years later by Woodrow Wilson’s Red Scare. In the constructed historical memory that has come down to us, capturing authentic and persistent aspirations, the strikers won under the banner “Bread and Roses” — sustenance and dignity. Today, immigrant activists in the US organize in the Immigrant Dignity campaign. The lively labor press of the early industrial revolution bitterly condemned the rising industrial system not just for its violence but for depriving those driven to the mills of their dignity as free human beings. That resounds to the present. The early 1970s witnessed the last militant strike wave in the US before the labor movement has once again been crushed under the neoliberal assault on the population, with Reagan and Thatcher playing a leading role. The strikes were a call for Bread and Roses, for workers control of the workplace so that they could uphold their basic dignity. That continues today with the spread of worker-owned enterprises and cooperatives on an impressive scale. These aspirations have been suppressed by violence throughout history, but the spark is never extinguished and continues to burst into flame.

The search for dignity is understood instinctively by those who hold the clubs, who recognize that apart from violence, the best way to undermine it is by humiliation. That is second nature in prisons, reaching its sordid extreme in places like Bagram and Guantanamo, portrayed unforgettably by Victoria Brittain, who has recently broadened the shameful picture to include the fate of the women left behind.

The normal practice in Israeli prisons has gained some attention today, because of the concern that it might spark another uprising after the death of a young man, Arafat Jaradat. He was arrested in his home at midnight, to properly intimidate the family, charged with having thrown stones and a Molotov cocktail a few months earlier during Israel’s November attack on Gaza. He was healthy and vigorous when arrested. He was last seen alive in court by his lawyer, who describes him as “doubled over, scared, confused and shrunken.” The Court remanded him to another 12 days of interrogation. He was found dead in his cell. Journalist Amira Hass writes that “The Palestinians do not need an Israeli investigation. For them, Jaradat’s death is much bigger than the tragedy he and his family have suffered. From their experience, Jaradat’s death isn’t proof that others haven’t died, it’s proof that the Israeli system routinely uses torture. From their experience, the goal of torture is not only to convict someone, but mainly to deter and subjugate an entire people.”

By humiliation, degradation, terror, familiar features of repression at home and abroad.

Europeans should not forget their willing participation in the latest phase of Washington’s reign of torture; “latest phase,” because of the ample precedents. The Open Society Institute just released its study “Globalizing Torture: CIA Secret Detentions and Extraordinary Rendition.” It reveals that 54 countries participated in this campaign, including most of Europe. One region of the world was exempt: Latin America. Virtually alone, it refused to participate in globalizing torture. That is a most remarkable fact. Only a few years ago Latin America still remained Washington’s obedient “backyard,” and one of the torture capitals of the world among other horrors in the course of Washington’s war against independence and freedom in the past half century. No longer. One can easily see why western elites are so concerned about the threat of democracy, and so committed to limiting it, most recently in the Middle East.

Western condemnation of the brutal treatment of dissidents in Russia’s domains knows no bounds, but one will have to search to find some recognition of the fact that from 1960 to “the Soviet collapse in 1990, the numbers of political prisoners, torture victims, and executions of nonviolent political dissenters in Latin America vastly exceeded those in the Soviet Union and its East European satellites,” quoting historian John Coatsworth in the Cambridge University History of the Cold War. Among the executed were many religious martyrs, victims of Washington’s dedicated war against the Church after Vatican II in 1962, which sought to restore the Gospels and its “preferential option for the poor.” The famous School of the America’s, which trained Latin American killers, proclaims with pride that the US army helped defeat liberation theology, which fostered the intolerable heresy.

The need for humiliating those who raise their heads is an ineradicable element of the imperial mentality. To cite just one instructive case, the highly regarded liberal commentator of the NYT Thomas Friedman, also a Mideast specialist, appeared in May 2003 in one of the rare discussion programs on US TV. He was asked by the host for his recommendations for the US-UK occupying army in Iraq. His answer was elegant and forthright:

“We needed to go over there, basically, and take out a very big stick right in the heart of that world. ... What [Muslims] needed to see was American boys and girls going house to house from Basra to Baghdad and basically saying ‘Which part of this sentence don’t you understand? You don’t think we care about our open society? You think this bubble [of terrorism] fantasy, we’re just going to let it grow? Well, suck on this!’” In short, a severe dose of humiliation administered by American boys and girls will teach the terrified women and children whose houses they break into that they had better stop terrorizing us.

As usual, it elicited little comment apart from the usual misguided sentimentalists.

The need not just to control but to humiliate the victims is second nature to political leaders as well. One case of some significance was in 1988, when the Palestinian National Council formally accepted the international consensus on a two-state settlement. The US by then was becoming an international laughing stock with its unwillingness to hear Yasser Arafat’s call for peaceful diplomacy. The reasons were explained by Secretary of State George Shultz in his memoirs. He informed his boss Ronald Reagan that Arafat was saying in one place “‘Unc, unc, unc,’ and in another he was saying, ‘cle, cle, cle,’ but nowhere will he yet bring himself to say ‘Uncle’,” in the style of abject surrender expected of the lower orders.

Israel did hear the call for a political settlement, and reacted by declaring that there can be no “additional Palestinian state” between Israel and Jordan — a Palestinian state by Israeli fiat, whatever the Arabs may think. Washington quickly endorsed Israel’s reaction, in the James Baker Plan of December 1989. All pretty much excised from history.

There is no need to sample the reflexive resort to the principle in imperial history. One case that has probably not been forgotten by the victims is the attitude of Anglo-Iranian Oil Company officials towards the “wogs” during the glory days of the company in Iran: the only way to handle them is “to browbeat them, to cow them into submission,” with the iron fist always poised when such gentler means do not suffice. Iran’s brave and dignified elected leader, Mohammed Mossadeq, was subjected to ugly abuse and humiliation by the British government and the educated classes, in the US too, because he sought to implement Iran’s right to take control of its own resources — “our resources,” as they are common referred to in internal documents, which by accident happen to be somewhere else. A dedicated constitutionalist, he kept to completely non-violent means, and paid for it with the US-UK military coup in 1953, greatly lauded in the West. The New York Times editors soberly explained that “Underdeveloped countries with rich resources now have an object lesson in the heavy cost that must be paid by one of their number which goes berserk with fanatical nationalism. It is perhaps too much to hope that Iran’s experience will prevent the rise of Mossadeghs in other countries, but that experience may at least strengthen the hands of more reasonable and more far-seeing leaders, who will have a clear-eyed understanding of the principles of decent behavior.” And it did, for many years, though by the 1970s the tide of independent nationalism could no longer be crushed by violence.

The attitudes are so close to the surface that they break through at the slightest provocation. That happened at once when the wogs asserted their rights in the early ‘70s and sought to overcome the sharp decline in oil prices relative to other commodities, which had been so beneficial to the West thanks to its effective controls. The influential intellectual Irving Kristol, one of the godfathers of contemporary conservatism, observed that “insignificant nations, like insignificant people, can quickly experience delusions of significance,” which must be driven from their primitive minds by force: “In truth,” he explained, “the days of ‘gunboat diplomacy’ are never over. ... Gunboats are as necessary for international order as police cars are for domestic order,” thoughts widely echoed.

The Israeli occupiers of what we should now call the State of Palestine have also understood very well the efficacy of humiliation as a weapon against the search for a dignified life. It has been a constant feature of the occupation, sometimes so outrageous that it breaks through to public attention. Thirty years ago political leaders, including some of the most noted hawks, submitted to Prime Minister Begin a shocking and detailed account of how settlers regularly abuse Palestinians in the most depraved manner and with total impunity. The prominent military-political analyst Yoram Peri wrote with disgust that the army’s task is not to defend the state, but “to demolish the rights of innocent people just because they are Araboushim living in territories that God promised to us;” Araboushim is the slang counterpart of “niggers” or “kikes.” One of Israel’s most eminent intellectuals, Boaz Evron, added sardonically that Israel should keep the Araboushim “on a short leash,” so that they recognize “that the whip is held over their head.” As long as not too many people are being visibly killed, then Western humanists can “accept it all peacefully, [asking] What is so terrible?”

There’s plenty of evidence that he captured western morality quite exactly. Sometimes humiliation can take slightly more subtle forms. One was the topic of a lecture here two years ago in honor of Edward Said, by Rashid Khalidi, with the title “Human Dignity in Jerusalem.” Khalidi discussed a project of the Simon Wiesenthal Center — dedicated to promotion of “human rights and dignity” — to build a “Center for Human Dignity” in Jerusalem. The site they chose is the Mamilla cemetery, the most venerated Muslim burial place in Palestine, where companions of the Prophet are reputedly buried, and many other honored figures. Parts had already been turned into a parking lot and the site of Israel’s Independence Square. In Muslim law, as in other religions, “the sanctity of cemeteries is considered eternal,” Khalidi comments.

The idea of desecrating a cemetery to construct a “Center of Human Dignity” could only occur to those so dedicated to humiliation of their victims that they cannot perceive what they are doing. An appeal to bar the project was denied by the Supreme Court.

Finally I’d like to turn briefly to how these themes arise in the foreign policy issues that are of prime significance for US policy-makers and the political class, at least if we judge by the presidential debates, the Chuck Hagel senatorial hearings, and the coverage they’ve received.

In the foreign policy debate, two countries predominated overwhelmingly: Israel and Iran. Obama and Romney vied with one another in proclaiming their undying loyalty to Israel, and in identifying Iran as the gravest threat to world peace. In the Hagel hearings, there were 136 mentions of Israel and 135 of Iran, with scattered mention of others: Hagel was berated — by the Republicans, a fact of some interest — for being insufficiently loyal to Israel and not sufficiently dedicating to bombing Iran if it does not soon capitulate.

In the case of Israel, there has long been a near unanimous international consensus on a diplomatic settlement, blocked by the US for 35 years, with tacit European acceptance. I’ve brought up some of the reasons. Contempt for the worthless victims is no small part of the barrier to achieving a settlement with at least a modicum of justice and respect for human dignity and rights. It’s not beyond imagination that the barrier can be overcome by dedicated work, as has been done in other cases.

On Iran, I’d like to recommend a fine talk by Jon Snow in June 2012, the Lord Garden Memorial Lecture, at Chatham House. Snow knows Iran well, and had much of interest to say. His main point was that the West must overcome its contempt for Iran and its people. He ended his talk by calling for “Esteem, Esteem, Esteem.” We should respect Iran, its history, its civilization, while also making it quite clear that we condemn its government. We should engage with Iran, with trade, with cultural interchange. He brings up one highly successful case, a cooperative exhibition of Iranian artistic treasures by the British Museum and Iran. Another example is an International Congress on HIV/AIDS in Teheran last October. At the latest meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, US participants in the conference described Iran as “a model for the rest of the region” in its response to AIDS and added that “We can learn a lot from what Iranians are doing,” also reporting that Iran’s efforts are now being severely hampered by the harsh sanctions.

But the most important step, Snow emphasized, would be to overcome the contempt that has guided the West for a century, primarily Britain, the US since it joined and largely replaced Britain in 1953 in overthrowing the parliamentary government and installed the harsh tyranny of the Shah. I won’t review the disgraceful record of contempt and purposeful humiliation. It is explored in depth in the most important scholarly study of the coup, Ervand Abrahamian’s highly revealing work, just appeared. It should evoke shame and deep regret in the US and Britain, and we should also remember that in the last 60 years, not a single day has passed when the US and Britain were not brutally punishing Iran, first by installing and backing the Shah, then by supporting Saddam Hussein’s aggression, followed by harsh sanctions and now the open threat of war — a violation of the UN Charter, if anyone cares.

The current issue is Iran’s nuclear programs. We may ask who shares the Western perception that this is perhaps the gravest threat to world peace. That’s easy to answer. The obsession is not shared by the non-aligned countries, most of the world, who continue their vigorous support for Iran’s right to enrich Uranium. It is not shared in the Arab world, where the population generally dislikes Iran, but does not consider it much of a threat. They do of course perceive threats: primarily Israel and the United States. The people, that is. Western commentary prefers to keep to the oil dictators, who do see Iran as a threat.

Secondly, whatever the threat is alleged to be, is there a way to address it short of sanctions that punish the population and war? One approach would be to try to renew the Teheran agreement of May 2010, when Iran accepted a Turkish-Brazilian proposal to send Low-enriched uranium to Turkey while the nuclear powers would satisfy Iran’s needs for its medical reactors. The US government and media bitterly condemned Turkey and Brazil for overcoming the gravest threat to world peace, and Obama immediately rushed through sanctions at the UN. The Brazilian foreign minister, rather annoyed, released a letter from Obama to President Lula da Silva proposing exactly what Turkey and Brazil had achieved, presumably in the expectation that Iran would reject the proposal, providing a propaganda point. The US refused to “accept Yes for an answer,” as observed by Mohammed El-Baradei, former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency. The regrettable incident was all glossed over rather quietly.

A broader approach to the problem was proposed by the Non-Aligned conference in Teheran last August, renewing a long-standing proposal to establish a nuclear weapons-free zone in the region (and more broadly a ban on weapons of mass destruction, WMD). The proposal, vigorously advanced by Egypt in particular, has such overwhelming international support that Washington has been compelled to express its formal agreement. The essence of the proposal is also supported by leading strategic analysts in Israel and the United States. The UN General Assembly has called for “establishing a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Middle East” (Dec. 2011, passed without vote”).

An opportunity to carry the program forward arose last December, when an international conference was to be held in Finland to move towards implementation, in accord with the decision of the 2010 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference.

In November, Iran agreed to attend. A few days later Obama cancelled the conference. The Arab states said they would proceed anyway. In January, the European Parliament passed a resolution that “deplores the postponement” of the meeting and calls on the conveners (US, UK, Russia, UN Secretary-General) and the member countries of the European Union to ensure that the conference takes place “as soon as possible in 2013.” A few days later the Islamic Inter-Parliamentary Union closed its meeting of 48 Islamic countries with a resolution, proposed by Iran, demanding that the Middle East be free of WMD and particularly nuclear weapons.

The core issue, of course, is that the US will not allow Israel’s nuclear weapons to be subject to discussion or inspection.

A few days after Obama cancelled the December conference, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution calling on Israel to join the NPT, 174-6. Joining Israel in voting No were the US, Canada, and a few US Pacific island dependencies. The US then proceeded to carry out a nuclear weapons test, once again banning international inspectors from the test site.

Shortly after, a meeting took place under the auspices of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, an offshoot of the Israeli lobby. According to an enthusiastic report in the Israeli press, Dennis Ross, Elliott Abrams and other “former top advisers to Obama and Bush” assured the audience that “the president will strike (Iran) next year if diplomacy doesn’t succeed.”

Americans cannot protest the failure of diplomacy and seek to end the gravest threat to world peace, for a simple reason: Hardly a word about these recent events has been reported in the United States, another illustration of how free speech can be restricted in a very free society, without government coercion. It appears that the same is true here.

There are other possibilities, but none can be seriously pursued unless we are at least willing to take seriously Jon Snow’s sensible counsel. Unless the powerful are capable of learning to respect the dignity of their victims, impassable barriers will remain, and the world will be doomed to violence, cruelty, and bitter suffering.