Indiendebatt den 18 april på ABF-huset.

Jan Myrdal fick inleda och ansåg sammanfattningsvis att det över huvudtaget inte skrivs särskilt mycket om Indien i västliga media inklusive Sverige. Och att informationsläget dessutom har försämrats, det var bättre på Palmes tid ansåg han. Arundhati Roy hade vid ett möte i London instämt i att Indieninformationen försämrats. Det dåliga informationsläget ansåg Jan Myrdal berodde på ekonomisk-politisk styrning, att "den som betalar kusken bestämmer färden":

– Någon "fri press" i största allmänhet tror jag inte det finns någon närvarande här som tror på. Det finns inte, ansåg Jan Myrdal.

– I min nya bok "Röd stjärna över Indien" (se recension i Fjärde Världen 3/2011) har jag påpekat att adivasierna i Indien sitter på en förmögenhet. Det pågår en kamp om dessa naturrikedomar, adivasis måste bort anses det. Men de vill inte bli avskaffade. Vilket har lett till en intensiv väpnad kamp.

– Vattenkraften bedrivs det en rovdrift på och man bedriver en kamp mot detta av ett slag som samerna borde fört för 300 år sedan, sa Jan Myrdal.

– Men när Indiens regering går emot läkemedelsföretaget Bayer stöder vi dem givetvis i det.

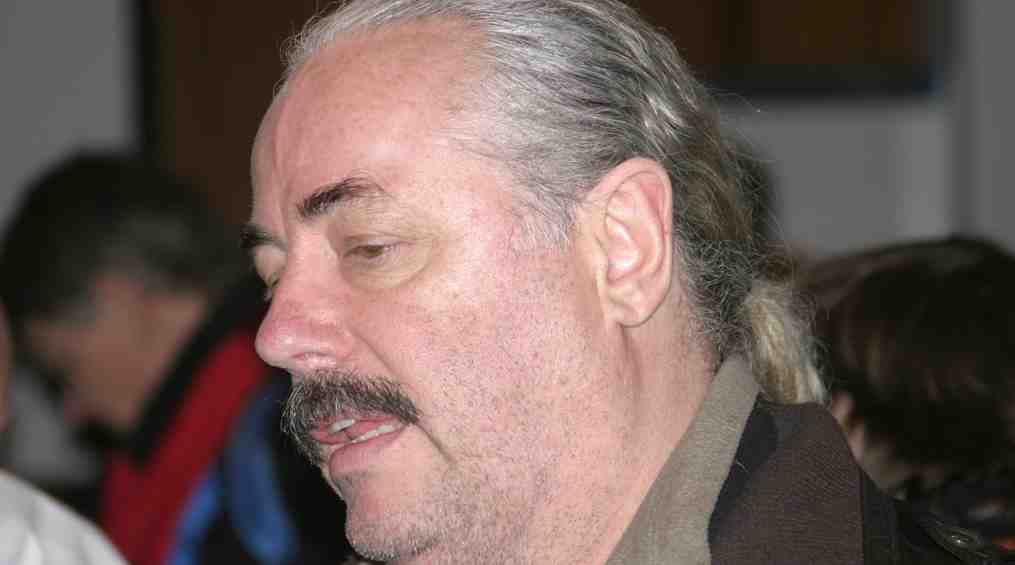

David Ståhl, ansåg att maoisternas kulor inte hade effekt mot korrruptionen. Foto: Ola Persson

David Ståhl höll inte med Jan Myrdal om att informationen om Indien varit bättre på Palmes tid, och ansåg att Arundhati Roy hade fel när hon sa att man "inte får" skriva om vissa saker i Indien.

– Dessutom finns svenska journalister placerade fast i Indien. Och de indiska tidningarna har fantastiska ledare.

– När det gäller fattigdomen så minskar den i Indien, men det finns fickor där den inte gjort det. Och det är där naxaliterna, maoisterna, Jan Myrdals kompisar, verkar.

De kan ibland göra saker som inte ligger i adivasiernas, ursprungsfolkens, intressen ansåg David Ståhl:

– Till exempel inrättade faktiskt bolaget Vedanta ett sjukhus i området nära de kända Nilgiribergen där dongria kondherna protesterat mot företagets planer. Men ingen personal vågar sig dit eftersom maoisterna hotat dem och sagt att de då kommer att agera.

– Ingen förnekar att vanstyre råder i Indien. Men Anna Hazare, en känd indisk personlighet, har med sin kampanj mot korruption åstadkommit mer på sex månader än vad maoisterna gjort på 30 år med sina kulor – och med mer varaktiga resultat!

P J Andersson höll delvis med Jan Myrdal ifråga om medieläget:

– USA-valet följs noga i svenska media, men inte indisk politik. Det blir en rundgång. Vi vet så lite om Indien, och därför blir det så lite intresse för Indien.

– Indiska media håller samtidigt en hög kvalité. Där finns en rå men frisk ton mot regeringen till exempel. I Sverige är underdånigheten från journalister påfallande mycket större, ansåg PJ Andersson:

– Det finns en offentlighetslag i Indien, Right to Information Act, och den står på folkets sida.

– När det gäller läskunnigheten i Indien så har den ökat snabbt. 74 procent är nu läs- och skrivkunniga. I Kina är det över 90 procent, men Indien har snabbt förbättrat sin siffra.

– Jag träffade några personer i Orissa som sa att: "naxaliterna är som samer, fast de har vapen". I delstater som Orissa och Uttar Pradesh finns ingen offentlig välfärd värd namnet. Men det är inte så enkelt att det bara är att ta upp vapen och slåss mot den indiska staten.

– Det finns aktivister som är gandhianer, många byar har vänt maoisterna ryggen.

– När det gäller adivasier – ursprungsfolken – och eftersatta kaster så har deras standard förbättrats snabbare än andra gruppers i Indien.

Christer Norström, frågade hur solidariteten med Indiens folk skulle utvecklas. Foto: Ola Persson

Hans Magnusson berättade om olika personer som haft betydelse för de "kastlösas" rörelser i Indien: dr Ambedkar, journalister, aktivister. Han nämnde också rörelsen Dalit Panthers:

– Kvinnorna utsätts för ett tredubbelt förtryck och diskrimineras utifrån kast, klass och kön.

– En aboriginkvinna sa vid ett tillfälle: jag vill inte ha din hjälp, men om du tror att din frihet är bunden till min, då är jag med.

FN och EU trycker på den indiska regeringen för att komma till rätta med diskrimineringen som daliterna utsätts för. Men man agerar inte i särskilt stor utsträckning, hävdade Hans Magnusson.

– När det gäller naxalitrörelsen och uppkomsten av ett "rött bälte" i östra Indien så bygger dess framgångar helt på att människor har tvingats iväg på grund av utvecklingsprojekt. Narmadaflodens dämningar, husdemoleringar.

– Det är bara en fjärdedel av Indiens befolkning som har dragit nytta av framstegen på senare år. Statistik från 2007 visade att 77 % av Indiens befolkning lever på 20 rupies (under 10 kronor) per dag, sa Hans Magnusson.

Hans Magnusson, till höger, påpekade att Indiens hundratals miljoner daliter inte fått bättre ekonomiska levnadsvillkor. Foto. Ola Persson

Christer Norström, socialantropolog som sysslat med Indien under de senaste 20 åren ansåg under frågestunden efter debatten att det bland Indiens bönder finns tre förhållningssätt: konfrontation, självmord eller förhandlingar:

– Vi kan stödja, hjälpa till. Frågan som måste besvaras är hur solidariteten med Indien ska komma till stånd?

Åhörarna gick hem kanske inte lugnade men med lite mer kunskaper. Arrangör av debatten var föreningen Indiensolidaritet i samarbete med ABF-Stockholm.

Text: Henrik Persson

Foto: Ola Persson

(Ur senaste numret av tidningen Fjärde Världen, nr 2-2012. Beställ via hemsida: www.f4world.org )

Den här e-postadressen skyddas mot spambots. Du måste tillåta JavaScript för att se den.

Gunilla Herlitz et al.,

DN har upplåtit en helsida till Per J. Andersson för att skriva om Jan Myrdal. Frågan är vad syftet är med artikeln – att tala om att Jan Myrdal blivit ”portat” i några länder och nu i år i Indien; eller Myrdals författarskap, eller Myrdals indologiska inställning – det blir litet av varje men utan fokus. Bara uttrycket ´portad´ ger ett raljerande tonläge. Men framförallt, artikeln ger ingen bakgrund eller försök till verklig information om det som Jan Myrdal beskriver i sin bok. Den allvarligaste kritiken vill jag rikta till Dagens Nyheter. Den enda bevakningen av Indien DN presterar är några artiklar i Indiens periferi; alltså ganska ytliga och föga lärorika. De kan vara sanna i sak men genom att bara upprepa sådana typer av nyheter blir bilden av Indien osann.

Om nu DN ställer en helsida till förfogande om Indien och då Myrdals bok om Naxalitrörelsen, varför då göra ett försök att försöka förstå och till läsarna förmedla varför en revolutionär rörelse kom till 1967 och fortköpande utvecklas och som Indiens premiärminister Manmohan Singh 2005 kallade för det allvarligaste interna hotet mot landets självständighet och därför sänt mer än 100 000 militär och mer poliser att bekämpa. Det, Gunilla Herlitz, är en undermålig nyhetsförmedling.

Jag bifogar två artiklar; en just klar om Naxalitrörelsen, och en artikel från 2006 om Daliternas situation. Med et vill jag säga, Gunilla Herlitz, att jag skriver gärna några artiklar för DN om Indien. Jag har de senaste 15 åren besökt Indien olika länga varje år sedan dess och har lärt känna den del av Indien som t.ex. Per J. Andersson eller de journalister DN brukar sända ut inte känner. Så om du verkligen vill skärpa bevakningen av Indien står jag till förfogande.

Hans

Hans Magnusson

Dalit Solidarity Network-Sweden (DSN-S)

DSN-S is a member of the International Dalit Solidarity Network (IDSN); a network organization consisting of national Dalit coalitions in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Bangladesh, national Dalit solidarity networks (DSN) in seven European countries and international associates working nationally and internationally to eradicate discrimination based on caste.

Tyvärr kan FiB.se endast bifoga en artikel som PDF med text och bilder.För båda PDF artiklarna:

Kontakta Hans Magnusson

Berättelser om förtryck och befrielse HM 2006-11-11 |

Hans Magnusson

2006-11-11

My final words of advice to you are educate, agitate and organize; have faith in yourself.

With justice on our side I do not see how we can loose our battle. The battle to me is a matter

of joy. The battle is in the fullest sense spiritual. There is nothing material or social in it. For

ours is a battle not for wealth or for power. It is battle for freedom. It is the battle of

reclamation of human personality…

- Dr. B. R. Ambedkar

Berättelser om förtryck och befrielse

Hur ska man förstå en så absurd samhällsordning, där kasttillhörighet sedan århundraden har

en avgörande roll för människors sociala och ekonomiska villkor och ställning i förhållande

till varandra? Denna artikel är ett försök att sammanfatta många hundra år av berättelser om

en samhällsgrupp på ca 170 miljoner människor, som kallar sig Daliter och som har

definierats som de ´oberörbara´ inom kastsystemet, om förtrycket och förnekelsen av dem och

deras förmåga att skapa en egen identitet som ett led i kampen för fullvärdigt medborgarskap

med rätt till mänsklighet, mänsklig värdighet och mänskliga rättigheter.

Ordet dalit betyder ordagrant krossad eller bruten i bitar men innebär i ett socialt

sammanhang att vara förtryckt och underordnad.

En väg till förståelse är att lyssna till Daliternas egna berättelser, Dalit Sahitya. I år har flera

berättelser av Daliter uttryckta i poesi, litteratur, bildkonst och aktivism av en lycklig

tillfällighet flutit samman till att kunna presenteras i ett sammanhang. På bokmässan i

Göteborg i september i år introducerades två böcker, Berättelsen på min rygg – Indiens daliter

i uppror mot kastsystemet (Ordfront) och Detta Land som aldrig var vår Moder (Tranan) med

dikter av indiska Dalit poeter och bilder av Dalit konstnären Savi Sawarkar. Redaktörer för

båda böckerna är Eva-Maria Hardtmann och Vimal Thorat i samråd med Tomas Löfström och

Birgitta Wallin, Indiska Biblioteket. Samma månad utsågs Ruth Manorama från Bangalore,

Indien till en av tre mottagare av Right Livelihood Award 2006 för sitt livslånga engagemang

för Daliternas frihet. Det är lätt att räkna in också aktivism som en form konst, åtminstone på

det sätt som den förverkligas av Ruth Manorama.

Böckerna ger inblick i hur kastsystemet upplevs av daliterna själva och vilka konsekvenser

det har för dem. De visar hur ord, bild och aktivism kan samverka för att skapa

självmedvetande, självkänsla och värdighet hos en tidigare utstött och förtryckt

samhällsgrupp. Ord och bild blir en länk till att minnas historien men ger också uttryck för en

förändrad innebörd av ordet ´dalit´ från att innebära förnekelse av mänsklig värdighet till att

stå för ett egenvärde där förnekelse byts till självrespekt och en tro på att kampen för

mänskliga rättigheter ska leda fram till ett värdigt liv.

Dalit Sahitya och Savi Sawarkars bilder ger röst åt dem utan egen röst men lägger också

grunden för dem att långsamt samla insikten och kraften att stå upp och hävda sin rätt så som

till exempel Sharankumar Limbale ger uttryck för i sin dikt Vitbok

Jag ber inte om

en sol eller måne

er gård, ert land,

era höghus eller palats.

Jag ber inte om era gudar eller ritualer, kaster eller sekter

Eller ens om era mödrar, systrar, döttrar.

Jag ber om

Mina rättigheter som människa.

--------------

Mina rättigheter: infekterade upplopp

som smittar stad efter stad, by efter by, människa efter människa.

För det är de rättigheter jag har –

avstängd, utstött, fängslad, förvisad.

Jag vill ha mina rättigheter, ge mig mina rättigheter!

Kan ni förneka detta inflammerade sakernas tillstånd?

Jag kommer att riva upp skrifterna som järnvägsräls,

bränna era laglösa lagar som man bränner en buss.

Mina vänner,

mina rättigheter stiger som solen!

Kan ni förneka själva soluppgången?

Savi Sawarkar, Voice for the Voiceless

Eleanor Zelliot (1992) i sin bok From Untouchables To Dalit menar att ordet dalit under

senare delen av 1900-talet kommit att användas i en helt ny kulturell kontext för att

representera ”… a new level of pride, militancy and sophisticated creativity” … “and an

inherent denial of pollution, karma, and justified caste hierarchy”.

Zelliot refererar också till Gangadhar Pantawane, språkprofessor och grundare av

Asmitadarsh (Mirror of Identity), som hon menar gett den tydligaste definitionen av

innebörden av begreppet dalit så som daliterna ser sig själva idag. Det står för ett radikalt

avståndstagande från den religiöst betingade legitimiteten av förtrycket. Pantawane säger: To

me, Dalit is not a caste. He is a man exploited by the social and economic traditions of this

country. He does not believe in God, Rebirth, Soul, Holy Books teaching separatism, Fate and

Heaven because they have made him a slave. He does believe in humanism. Dalit is a symbol

of change and revolution.

Denna aktivistiska innebörd av begreppet har också den rörelse som bildades under 1970-

talet, Dalit Panthers, starkt bidraget till. De hämtade sin inspiration från de svartas

frigörelsekamp i USA under 1970-talet, Black Panthers i USA fick sin motsvarighet i Dalit

Panthers i Indien, i första hand i delstaten Maharashtra i västra Indien. Ordet dalit

omvandlades från att referera till de förtryckta i passiv mening till att associeras med

aktivism, självrespekt och motstånd.

Dalitrörelsen i den form som National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights i Indien och den

internationella rörelsen för solidaritet med Daliter (International Dalit Solidarity Network,

IDSN) utgör har sedan ett tiotal år organiserat sig nationellt och internationellt, vilket fört

frågan om kastbaserad diskriminering (discrimination based on work and descent) till både

FN och EU. Det internationella lobbyarbetet har utan tvekan haft framgångar. Exempel på

detta är beslutet av FNs kommission för mänskliga rättigheter (nuvarande Rådet för

Mänskliga Rättigheter) i april 2005 att utse två speciella rapportörer med uppgift att utreda

frågans omfattning och orsaker och lämna rekommendationer till kommissionen för hur denna

typ av kränkningar ska undanröjas. Ett annat exempel är att en kommitté under

Europaparlamentet den 18 december i år ska ha en hearing i frågan med representanter från

dalitrörelsen.

Kast som samhällsordning

Vad är kast och hur kom det sig att ett samhällssystem byggt på kaster alls uppstod? Inget

samhällssystem kommer till utifrån en väl genomtänkt modell. En social struktur uppstår och

påverkas av enskilda omvälvande omständigheter och utvecklas över en längre tid. Till slut

har den fått en klar och tydlig form och får sin legitimitet från ett avlägset förflutet, då de

ursprungliga händelserna för dess tillkomst är gömda under myter och legender. Vid det

tillfället intar den ett rationellt utformat system för ett samhälles organisation. Den hinduiska

samhällsordning, där kastsystemet ingår som en bärande princip, bör ses i ett sådant

sammanhang.

Ordet kast kommer från det portugisiska ordet casta, som närmast betyder börd eller härkomst

genom födsel. En kast i denna betydelse består av grupper som knyts samman genom yrke

och val av äktenskapspartner inom gruppen. De portugisiska bosättarna kring provinsen Goa

i mitten av 1500-talet observerade att befolkningen var indelade i olika castas av skiftande

rang, som upprätthölls så strikt att ingen med högre status kunde äta eller dricka med någon

av lägre börd och Garcia de Orta noterade 1563 att sönerna följde sina fäders yrken.

Termen kast har kommit att användas om de två indiska begreppen varna (färg) och jati

(födelse).

Samhällsordningen började ta form under den vediska perioden 1200 – 500 f. Kr. Då lades

grunden för den hierarkiska rangordningen av människor i de fyra varna som genom

århundradena getts en religiös legitimering. Jati-tillhörigheten kom under historiens gång att

bindas samman med varna kategorierna.

Enligt legenden i Veda skrifterna, RgVeda 10.90, (Purushasukta, the Hymn of Man) skapade

gudarna universum inklusive samhällets fyra klasser (varnas) genom att offra och söndra

Purusha, urmänniskan. De skapade en Brahmán (präst, lärare) ur hans mun, Kshatriya

(krigare, aristokrat) ur hans båda armar och Vaishyas (köpmän, handelsmän) ur hans lår. De

utgjorde de två gånger födda (twice born, den biologiska och den rituella). En fjärde varna,

Shudra (med uppgift att tjäna de högre varna) skapades ur hans fötter.

Panchamas, en femte grupp, de ´oberörbara´, de som utför de ´orena´ arbetsuppgifterna och

därmed uppfattas och behandlas som ´orena´ i religiös och rituell mening, kom att få sin plats

under och utanför de fyra varna. De står utanför varna systemet men de har en kasttillhörighet

genom att ingå i en jati.

Jati är ett uttryck för födelse, härkomst och sammanhållningen eller gemenskapen i en grupp,

en släktskapsorganisation, där medlemmarna traditionellt utövar ett eller ett par näraliggande

yrken. Läderarbetare, krukmakare, tvättare, boskapsuppfödare och lantarbetare i ett område

till exempel utgör var för sig olika jati. Denna gemenskap brukar också begränsa området för

val av äktenskapspartner. Alla individer tillhör därmed en jati. Det är dessa företeelser som

kan sägas definiera begreppet kast. Det finns flera tusen olika jatis och antalet medlemmar i

en särskild jati kan variera från några tusen till flera miljoner människor.

Då antropologerna under 1960-talet började studera och försöka förstå den sociala strukturen

kunde de iaktta den mångfald av olika jati (kastgrupper), som förekom i olika samhällen i

Indien. I likhet ned de hierarkiska förhållandena mellan de fyra varnas, så som dessa

framställdes i de vediska skrifterna, fann de att relationen mellan de olika jatis var

strukturerad på ett motsvarande sätt efter religiösa föreställningar om ´renhet´ och orenhet´.

Det är inte helt klart hur den ursprungliga rangordningen mellan de olika jatis såg ut, inte

heller till vilken varna de hörde. I den folkräkning som den brittiska kolonialmakten lät

genomföra vart tionde år från 1901 ingick i att alla skulle uppge både sin varna och jati

tillhörighet. Detta kan ha bidragit till att förstärka kastsystemet och göra det mer statiskt.

De olika jatis kom på så sätt att kopplas samman med det på religiösa grunder hierarkiskt

arrangerade varna systemet. Så får jatis som tillhör de högre varna högre status än de jatis

som räknas till shudras eller de ´oberörbara´. Dessa föreställningar länkade samman

respektive åtskilde de olika jatis i alla tänkbara relationer. Det kan gälla val av

äktenskapspartner, yrkesval kopplat till det material man använder, med vilka man äter och

dricker. De ´oberörbara´ ingick i sådana jatis, som med hänvisning till deras yrkesutövande,

uppfattades som det mest ´orena´ och var därmed fysiskt uteslutna från så gott som alla

sociala relationer, aktiviteter och platser.

Panchamas, de ´oberörbaras´, utanförskap och behandlingen av dem som ´oberörbara´ kom

att förtydligas och religiöst legitimeras i efterföljande vediska skrifter och i de smrti skrifter,

som utgörs av mytologiska skrifter och lagböcker.

Under Upanishad perioden, 800 till 600 f. Kr kom människors sociala ställning att förklaras

after principerna om karma och själavandring. Människors handlingar i tiden hade

konsekvenser för framtiden. Med kombinationen av karma och själens vandring till en ny

människokropp i ett flertal omgångar kunde man rättfärdiga att den social status en människa

har beror på hans handlingar i ett tidigare liv. Så kan också ´oberörbarheten´ förklaras och

rättfärdigas. I texten Chandogya Upanishad 10:7 talas inte bara om de tre högre varna utan

också om Chandalas (de utstötta), som jämförs med en hund eller ett svin:

Accordingly, those who are of pleasant conduct here the prospect is, indeed, that they will

enter a pleasant womb, either the womb of a Vaishya. But those who are of stinking conduct

here the prospect is, indeed, that they will enter a stinking womb, either the womb of a dog, or

the womb of a swine, or the womb of an outcaste (chandala).

De episka skrifterna Ramayana (ca 400 f. Kr.) och Mahabharata (the Pandu hero, 600-200 f.

Kr. och om Krishna, the divine hero 200 f. Kr-500 e.Kr.) ger tydliga uttryck för hur villkoren

för Daliterna, de ´oberörbara´, hade förvärrats. I dessa texter görs hänvisningar till den status

som tillskrivs både den fjärde varna, Shudras; och de utstötta, de ´oberörbara´, som är

förbjudna att lära sig läsa och skriva eller utöva religiösa riter. Bhagavad Gita bekräftar

föreställningen om de fyra varna (chaturvarnyam) och berättar att Lord Krishna har skapat

dessa. Den uppmanar också medlemmarna av respektive kast att troget utföra de plikter som

deras kasttillhörighet föreskriver.

En senare skrift, som fastställde graderingen mellan de olika varna är Manusmrti, Manus Lag

från vår tids första århundrade. Med denna skrift fråntas ´den femte kategorin´, de

´oberörbara´ en samhällelig identitet och deras utanförskap befästs. Lagen, som består av

2 685 verser, föreskriver grunderna för ett idealt socialt samhälle genom att fördela plikter och

rättigheter mellan de olika kasterna. Ordningen vilar på tre samverkande faktorer; en för varje

kast genom födelsen förutbestämd och evig fördelning av arbetsuppgifter; en ojämlik och

hierarkisk fördelning av sociala och ekonomiska rättigheter till exempel ägande av jord,

anställning, lön, utbildning; samt att ordningen behålls genom en serie sociala och

ekonomiska tvångsmedel. Innebörden av denna ordning är att den grupp, som befinner sig

högst i hierarkin, brahmaner, har alla rättigheter och den grupp, som är längst ned, de

´oberörbara´, har inga rättigheter. När sådana föreställningar genom århundradena får fäste i

människors sinnen finns ett inbyggt motstånd mot förändringar, också hos dem som tillhör de

exploaterade kasterna.

Savi Sawarkar, Manu

Savi Sawarkars ger bilden av Manu ett strängt ansiktsuttryck som är analogt med den sociala

struktur som genomsyrar kastsystemet. Linjerna och prickarna i Manus ansikte påminner om

kobraskinnets teckning och märkena i hans panna liknar märkena på kobrans huvud. Ormen

med dess gift är en metafor för ondskan. Manus lagar är förkroppsligad ondska symboliserad

av medaljongen kring hans hals.

Att våga tro på förändring – ett hotfullt scenario

Den sociala och fysiska segregeringen mellan de olika kastgrupperna lever i stor utsträckning

kvar i det indiska samhället. Grundlagen och andra lagar förbjuder diskriminering på grund av

´oberörbarhet´. I lagteknisk mening är därmed ´oberörbarhet´ avskaffad, men i verkligheten

lever den kvar. De medvetna av de tidigare ´oberörbara´ kallar sig daliter men i stor

utsträckning är fortfarande kasttillhörigheten avgörande som identitet. Likaså lever de

traditionella införlivade vanorna vidare, möjligen så att de nu utgör en blandning av kast- och

klasstillhörighet. Fortfarande kan byarna vara delade, där daliterna lever utanför den centrala

byn, hämtar vatten i sin egen brunn och där fysisk kontakt med en person av högre kast till

exempel genom bruk av samma teglas eller vattenkälla ses som förorenande. Lagen om allas

tillträde till templen missbrukas likaså.

Också i städerna lever kast-kulturen vidare. Alla, oavsett kast är fria att slå sig ned i städerna.

Men fröet till kattillhörighet flyttar med och man slår sig helst ned i områden med människor

av samma kast. Daliter kan ha gjort en klassresa och leva ett hyggligt medelklassliv, särskilt

bland stadsbor, men inte en motsvarande kastresa, vilket ju inte är möjligt, ty det kast man

tillhör är evig och styr fortfarande stora delar av människors liv och i byarna lever

konsekvenserna av kastsystemet ofta kvar i traditionella former. Ett genom århundraden så

införlivat hierarkiskt socialt system tycks vara svårt att utrota. Industrialiseringen må ha brutit

den tidigare yrkesidentitet som tillsammans med härkomst (födelse) var knuten till en särskild

kast (jati) men den bryggar inte över kastgränserna. De rituella föreställningarna baserade på

´renhet´ och ´orenhet´ är mer bestämda av härkomst än av yrke.

Dalitrörelsen har haft framgångar i sitt internationella lobbyarbete, men den avgörande frågan

är naturligtvis vad som händer i Indien och andra länder där kastbaserad diskriminering

förekommer. Det kan vara lätt att förledas till att tro att i ett land som Indien, med en

demokratisk författning och en under många år stark ekonomisk tillväxt, ska ha förmåga att

lösa de sociala problem som förekommer. I Indien finns en medelklass på ca 300 miljoner

med en relativt god standard, en hightech industri i världsklass. Landet intar en växande plats

i den ekonomiskt globaliserade världen genom handelsutbyte och ett positivt mottagande av

outsourcing från de industrialiserade länderna i väst och är också en kärnvapenutrustad stat

som pockar på plats bland världens stormakter. Den sociala verkligheten för majoriteten av

befolkningen är emellertid en annan och pekar snarare på en i många stycken förvärrad

situation för de grupper som är de mest drabbade, daliter, stamfolk (adivasis) och andra

eftersatta grupper. Det visas inom olika samhällsområden; utbildning, hälsovård, barn och

kvinnors situation, övergrepp och våld mot utsatta grupper och rättsväsendets bristande

legitimitet.

Right to Food är en 500-sidig bok utgiven av Human Rights Law Network i Delhi. Den

bygger på en genomgång av Supreme Court Orders, Commissioners Reports, National Human

Rights Commission Reports och ett antal artiklar. Författarna summerar att kampen för den

grundläggande rätten till mat till alla i högsta grad är en fortsatt kamp: man har haft framgång

genom ett antal beslut i Supreme Court men utgången av kampen är fortfarande oviss. Hunger

och även svält förekommer i en oroande stor omfattning. I december 2000 skrev

centralregeringens minister för konsumentfrågor till delstatsregeringarna och meddelade att

fem miljoner människor var offer för svält. Hälften av Indiens barn är undernärda. År 1998

rapporterades hundratals människors död av svält och 2001 rapporterade People´s Union for

Civil Liberties beträffande Rajasthan att förhållandena var oförändrade. Samtidigt finns ett

överskott av spannmål lagrade men hindras från att fördelas genom oklar beslutsgång,

byråkrati och en snedvriden ekonomisk lönsamhetslogik. Reformer som ska garantera ´mat

mot arbete´, 100 dagar per år, har inte genomförts. Globaliseringen har medfört att

spannmålsarealen minskat och att regeringen skurit ned finansieringen av landsbygdens

utveckling från 11,6 % av BNP till 9,1 %, vilket har bromsat tillskotet av arbetstillfällen, samt

att högre kostnader för bekämpningsmedel och gödningsmedel kraftigt har försvårat för

mindre jordbruk att överleva.

The Human Rights Magazine Combat Law (April-May 2004) redovisar försämrade

förhållanden inom flera områden. Ett av elva barn dör före fem års ålder. En sjukdom som

diarré som är lätt att förhindra skördar 700 000 barns liv varje år. Rinnande vatten hemma

saknas av 100 millioner hushåll och 150 millioner hushåll saknar elektricitet. Privatisering

och marknadsanpassning, i linje med Världsbankens och IMFs rekommendationer, av

hälsovård, utbildning och vatten försvårar ytterligare för Indiens fattiga att få tillgång till

dessa nödvändiga tjänster. Det offentligas kostnader för utbildning föll från en topp på 4,4 %

av BNP år 1989 till 2,75 % 1998-99 samtidigt som regeringen backat från sitt löfte att se till

att alla barn skall få en god kvalitativ utbildning. Motsvarande försämring kan avläsas inom

hälsovården.

Även om det inte är ovanligt att daliter idag har andra arbeten än de som deras föräldrar

utövade är det fortfarande vanligt att daliter utför traditionellt diskriminerande yrken. Manuell

rengöring av torrlatriner är ett sådant. Denna form av arbete är sedan många år genom lag

9170372225_65

förbjuden och delstaterna är ålagda att installera vattentoaletter med fungerande avlopp.

Genomförandet av lagen är emellertid trög.

Fysiska övergrepp mot daliter, våldtäkter av dalit kvinnor, ekonomisk och social

diskriminering är fortfarande vitt spridd och polisens och domstolarnas låga kapacitet gör att

förövarna ofta kommer undan utan rättegång och påföljd. Alltför många människor har

förlorat tilltron till att politikerna ska ta sitt ledaransvar för att förbättra villkoren. Frågan står

öppen om vilken väg det indiska samhället ska gå.

En någorlunda säker förutsägelse är att det kommer fler berättelser från nya generationer av

daliter. Och frågan är om dessa berättelser enbart kommer att skrivas med pennan som

redskap eller om förtrycket och ointresset från officiellt håll drivs så långt att pennan byts mot

svärdet. Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, daliternas ledare under första hälften av 1900-talet och

ordförande i den kommitté som författade förslaget till Indiens konstitution, pekade i sitt tal

till den konstituerande församlingen i november 1949 på den motsägelse, som fanns inbyggd i

det indiska samhället. Med den nya konstitutionen, menade han, fick Indien politisk

demokrati men saknade alltjämt social demokrati i betydelsen frihet, jämlikhet och

broderskap. Ambedkar avslutade sitt tal med denna varning: We must remove this

contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will

blow up the structure of political democracy which this Assembly has so laboriously built up.

Den varningen är berättigad också idag; och den får extra relevans i och med att så många

förtryckta människor har väckts till insikt om förhållandena och frustrerat och förgäves väntar

på den politiskt utlovade förändringen. Det finns skäl att tolka Gangadhar Pantawane´s ord i

det sammanhanget; Dalit is a symbol of change and revolution.

Berättelsen på min rygg

Boken Berättelsen på min rygg – Indiens daliter i uppror mot kastsystemet är en antologi i tre

delar, som hålls samman genom det gemensamma temat om daliter. I den första delen återger

åtta Dalit författare i novellens form sina egna och sina föräldrars upplevelser av

kastsystemet. Den andra delen tar upp den historiskt spännande konflikten mellan B. R.

Ambedkar (1891 – 1956) och M. K. Gandhi (1869 – 1948) under 1930-talets förberedelser för

ett självständigt demokratiskt Indien. Bokens tredje del innehåller tolv texter från samtida

dalitaktivister.

Den symboliska innebörden av bilden av B. R. Ambedkar på bokens omslag har sin egen

historia. Ambedkar utgöra den gemensamma nämnaren för bidragen i såväl denna bok som i

boken, Detta Land som aldrig var vår Moder. Bilden visar Ambedkar i olika situationer av

hans liv från de personliga händelserna som födelse och äktenskap till hans offentliga uppdrag

som advokat, justitieminister i Jawaharlal Nehrus första regering och som ordförande i den

kommitté som författade Indiens konstitution. Ambedkar, själv dalit, var den samlande

personligheten under första hälften av 1900-talet för daliternas kamp för fri- och rättigheter

och han inspirerar också idag dalitrörelsen i den fortsatta kampen för samma rättigheter.

Statyer av Ambedkar är en vanlig syn i Indiens byar och städer och en bild av honom finns

ofta på väggen i daliters hem. Den 14 april, dagen för hans födelse, firas numera också

officiellt.

Boken har tagit sin titel från en berättelse av Omprakash Valmiki, som berättar om sin

barndom och skolgång i en by åtta år efter självständigheten. Den består som alla bidragen i

antologin av flera berättelser, om förödmjukelse och misshandel men också om vrede, mod

och motstånd.

Omprakash familj tillhörde kasten chuhra, en oberörbar soparkast och de utförde alla slags

arbeten åt de landägande bönderna, städning, lantarbete och annat grovarbete, mot låg eller

ingen ersättning. Med självständigheten skulle de statliga skolorna officiellt vara öppna också

för de lågkastiga. Omprakash pappa såg till att han fick plats i en statlig skola, där han fick ett

allt annat än välkomnande mottagande. Han fick sitta långt från de andra barnen på golvet.

Han fick stryk av både pojkarna och läraren. Han fick inte dricka vatten ur brunne eller ur ett

glas utan vattnet hälldes i hans kupade händer en bit ovanifrån för att händerna inte skulle

beröra och ´orena´ glaset.

Soparungen hade ingen plats i skolan enlig deras syn. Vid ett tillfälle beordrade rektorn

honom att sopa först klassrummen och sedan hela skolgården, en uppgift han fick tre dagar i

rad. Den tredje dagen kom hans pappa förbi. Omprakash berättar … ”far ryckte kvasten ur

handen på mig och slängde iväg den. Hans ögon gnistrade. ´Vem är din lärare? Var är den son

av Dronacharya som tvingar min son att sopa´”. Aldrig glömmer jag, säger Omprakash, med

vilket mod och viken styrka min far trotsade rektorn den dagen; det var av stor betydelse för

hela min personlighet. Fadern tar hjälp av byäldsten och sonen kan fortsätta i skolan.

Vid ett tillfälle dristar sig Omprakash att jämföra sin egen och sin kasts situation som

oberörbara med en historia om hunger och fattigdom hämtad ur det hinduiska eposet

Mahabharata, som läraren berättar. Hela klassen stirrade på mig, skriver Omprakash, och

magistern röt. ”Nu stundar de yttersta tider när en oberörbar vågar sätta sig upp mot sin

lärare” Sedan befallde han mig att inta murga – kycklingställning. Det innebär att man hukar

sig ned, sticker armarna innanför låren, böjer ned huvudet och griper med båda händerna om

öronen. Läraren tar en käpp och straffar honom: ”Din soparunge, hur vågar du jämföra dig

med Dronacharya? Här får du för det … och här! Jag ska nog skriva en bok om dig ska du se

… på ryggen på dig!” Och så, säger Omprakash, skrev han en berättelse på min rygg med en

rad snärtiga käppslag och där står den fortfarande att läsa, rad för rad. Berättelsen om min

ungdom, om hungern och hopplösheten, om underklasslivet i ett feodalt samhälle, är inte bara

inetsad i min rygg utan även i min hjärna.

Den tredje delen av boken presenterar ett urval av aktivisters texter från början 1970-talet, då

Dalit Panthers publicerade sitt manifest fram till 2000-talets, då dalitrörelsen blivit en del av

den globaliserade rättviserörelsen. Bland författarna finns gräsrotsaktivister, journalister,

akademiker, politiker och teologer. Gemensamt för dem alla är att de i arvet från Ambedkar

vänder sig bort från kastsystemet och hinduismen. Texterna tar upp skilda teman som

nationen Indiens och omvärldens tystnad, om oberörbarheten och diskrimineringen, om

dalitkvinnorna som trefaldigt alienerade och patriarkatet, om påtvingad identitet, om politiska

landvinningar, om det konfliktfyllda systemet med kvotering för de lägre kasterna, om

dalitrörelsen som effektiv lobbyorganisation och om daliterna i en globaliserad värld.

Dalitaktivisterna har deltagit i det årliga World Social Forum sedan starten 2001. År 2004

organiserades WSF i Mumbai med ett avsevärt deltagande av daliter och blev då genom

massmedias bevakning mer kända över världen. Daliterna har blivit en dal av den globala

rättviserörelsen med vidare identifiering och solidaritet med förtryckta grupper världen över,

som ger förutsättningar för en gemensam analys av och kamp mot förtryckande socio-

politiska och ekonomiska strukturer.

Foto: Hanna Sandberg, Ruth Manorama, World Social Forum, 2004

De litterära bidragen, Ambedkars gärning, aktivisternas texter och Savi Sawarkars bilder i

boken Detta land som aldrig var vår moder utgör tillsammans starka berättelser om kampen

mot ett kast- och klassförtryck som kan väcka förnyad kampvilja hos varje människa med

någorlunda insikt i vår tids socialt, ekonomiskt och politiskt så ojämlika värld.

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar

Med tanke på den betydelse Ambedkar har ännu 50 år efter sin död finns skäl att ge en

närmare presentation av honom.

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (1891 – 1956) växte upp i delstaten Maharashtra. Hans familj

tillhörde kasten mahar, en tjänarkast bland de ´oberörbara´. Bhimraos far tjänstgjorde fram till

1892 inom den brittiska armén, där utbildning för anställdas barn var obligatorisk. Fadern,

som insåg värdet av utbildning, såg till att hans barn fick plats i byskolan. Här upplevde

Ambedkar för första gången själv det stigma hans kast var utsatt för. Han tilläts inte sitta inne

i klassrummet och hans lärare rörde vare sig honom själv eller hans böcker för att undvika att

bli ”orenad”.

images6

Bhimrao Ambedkar fick möjlighet att fortsätta sina studier. Han fick stipendier och läste först

vid Columbia University i USA och sedan vid London School of Economics och tog

doktorsgrader i ekonomi och juridik. I augusti 1947 utsågs han till justitieminister i den första

regering som Jawaharlal Nehru bildade efter själständigheten. Han lämnade den posten 1951

då han inte fick stöd av kongresspartiet för sitt reformförslag, the Hindu Code Bill, vilket

syftade till att liberalisera de sociala villkoren för kvinnor. I samband med sin avgång

uttryckte han sin besvikelse över hur de ´oberörbara´ behandlades i Indien. Som en slutgiltig

protest beslöt Ambedkar strax före sin död år 1956 att lämna hinduismen. Han ledde då en

massomvändelse till buddhismen i Nagpur i delstaten Maharashtra. Med denna händelse som

förebild har nya massomvändelser särskilt under 1990- och 2000-talen genomförts. Några av

hans sista offentliga ord i november 1956 löd:

The greatest thing that Buddha has done is to tell the world that the world cannot be reformed

except by the reformation of the mind of man, and the mind of the world.

Dr. B. R. Ambedkar

I Berättelsen på min rygg presenteras Ambedkars bok Buddha och hans dharma (Buddha

and His Dharma), som är en av hans mest kända verk. Ambedkar gör där sin egen tolkning av

buddhismen, som kommit att kallas Ambedkar-buddhism. Den är skriven med Indiens daliter

i åtanke. Innehållet har en socialistisk prägel och har kommit att liknas vid befrielseteologi i

andra delar av världen. Han gör i boken åtskillnad mellan religion och Buddhas dhamma.

Syftet med religionen, menar han, är att förklara ursprunget till världen; dhammas syfte är att

omstrukturera världen i en anda av förståelse och kärlek. Ambedkar gör också en personligt

färgad jämförelse mellan buddhismen och marxismen. Han ser likheter mellan dessa på fyra

plan; tid bör inte slösas på att förklara världens uppkomst utan snarare på att förändra den; det

finns en intressekonflikt mellan klasser; privat ägande ger makt åt en klass men skapar

lidande för an annan; för samhällets bästa bör lidande avlägsnas genom att privat ägande

avskaffas. Ambedkar var en stark förespråkare för landreformer och insatser för industriell

utveckling och för statens framträdande roll för ekonomisk utveckling.

Introduktionen av Ambedkar i Berättelsen på min rygg är en intressant och tankeväckande

läsning och inspirerar till att fördjupa sig i Ambedkars omfattande författarskap.

Ambedkar är framförallt känd för sitt agerande i samband med två för Indien betydelsefulla

händelser. Den ena gäller Indiens konstitution, som utarbetades efter självständigheten och

den andra gäller hans ledarskap från tidigt 1930-tal för de ´oberörbaras´ sak.

. Indiens konstitution

Ambedkar var ordförande i det utskott under den konstituerande församling, som från 1946

till 1949 utformade Indiens konstitution. Förslaget till konstitution antogs av parlamentet den

26 november 1949 och fick sin giltighet från den 26 januari 1950. Den dagen föddes den

demokratiska republiken Indien, en dag som varje år högtidlighålls som the Republic Day. I

konstitutionen slås fast att Indien är en sekulär och parlamentarisk demokrati och den lägger

grunden för maktfördelning mellan lagstiftande, verkställande och dömande funktioner. I

konstitutionen finns ett kapitel om grundläggande fri- och rättigheter, där bl a diskriminering

baserad på ´oberörbarhet´ förbjuds.

Indien hade kämpat sig till självständighet och genom konstitutionen definierat sin politiska

demokrati. Men innebar det också att Indien etablerat en social, samhällelig, demokrati? I sitt

tal inför den konstituerande församlingen den 25 november 1949 pekade Ambedkar på den

motsägelse, som fanns inbyggd i det indiska samhället. Han menade att Indien med den nya

konstitutionen fått politisk demokrati men fortfarande saknade social demokrati i betydelsen

frihet, jämlikhet och broderskap:

”We must make our political democracy a social democracy as well. Political democracy

cannot last unless there lies at the base of it social democracy. What does social democracy

mean? It means a way of life which recognizes liberty, equality and fraternity as the principal

of life. […] On the 26th of January 1950, we are going to enter into a life of contradictions. In

politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In

politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man one vote and one vote one value. In

our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure,

continue to deny the principle of one man one value. […] We must remove this contradiction

at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer from inequality will blow up the

structure of political democracy which this Assembly has so laboriously built up”.

. Kampen för de ´oberörbara´

Historien om Amedkars liv och gärning är också historien om Indiens millioner ´oberörbara´.

Inspirerad av den amerikanska jämställdhetsförklaringen och med sin ideologiska övertygelse

och sin personlighet blev Ambedkar ledare för daliterna, de förtryckta, som i honom fann en

orädd förespråkare för deras sak oavsett vem han kritiserade, Nehru, Gandhi eller kongress-

partiet. Hans vapen var juridiska och politiska, hans anatema var det exkluderande hinduiska

kastsystemet, och hans ambition var att förverkliga medborgerlig demokrati. Hans kamp för

jämställdhet började 1924 då hans bildade the Council for the Welfare of the Outcastes.

Ambedkar ansåg, att den enda möjligheten att förändra villkoren för de ´oberörbara´ var att

erövra den politiska makten och bildade under sin livstid flera politiska partier med program

för omfattade socioekonomiska reformer.

I sin kamp för de ´oberörbaras´ fri- och rättigheter hamnade Ambedkar i motsatsställning till

Gandhi. Båda ansåg sig företräda de ´oberörbara´. De hade dock olika syn på såväl orsakerna

till diskrimineringen av denna samhällsgrupp som om medlen att komma till rätta med

problemet. Skillnaderna var så stora att det ledde till en oåterkallelig konflikt mellan dem.

Ambedkar såg kastsystemet så nära knutet till hinduismen att det är omöjligt att komma ifrån

den ojämlikhet som är följden av systemet utan att också ta avstånd från religionen.

Han ledde flera icke-våldsdemonstrationer mot de kastregler som diskriminerade de

´oberörbara´ och vars viktigaste regel är att inte i något socialt eller religiöst sammanhang

tillämpa kastblandning. År 1927 ledde han en demonstration i Staden Mahad söder om

Bombay där deltagarna symboliskt drack vatten ur en damm som de ´oberörbara´ inte hade

tillträde till. Samma år kallade Ambedkar till en ny konferens i Mahad och lät då offentligt

bränna Manusmriti (Manus Lag), den lagbok från ca år 700 e Kr som innehåller kastregler

och som för Ambedkar var en symbol för den sociala orättvisa som kastsystemet innebär.

Icke-våldsaktionen vid Mahad ses av de Daliterna som början på deras politiska uppvaknande.

Den mest omfattande icke-våldsdemonstrationen med krav att få tillträde till templen ägde

rum vid Kala Ram Temple, en vallfartsort för pilgrimer i Nasik nära Bombay. Den

organiserades av Ambedkar och lokala ledare. Tusentals ´oberörbara´ deltog.

Demonstranterna möttes av motstånd inte bara från renläriga hinduer men också från lokala

medlemmar av kongresspartiet. De fem årens kamp, 1930 - 1935, för att få tillträde till

templen misslyckades. Amedkar tog 1935 definitivt avstånd från hinduismen och

tillkännagav, att fastän född som hindu, skulle han inte dö som hindu. År 1956 konverterade

han till buddismen. I staden Nagpur i Maharashtra konverterade vid detta tillfälle 300 000 av

hans anhängare.

Gandhi ansåg att ´oberörbarhet´ var ett religiöst snarare än ett socialt problem. Han ville

reformera kastsystemet men inte avskaffa det. Han trodde på ett jämlikt varna system och gav

sitt stöd till de ´oberörbaras´ krav att få tillträde till templen men han gjorde det på ett sätt som

inte skulle kränka de högre kasterna. Han betonade att det var nödvändigt att bevara

indelningen i kaster, som han menade ger social harmoni och stabilitet och en naturlig

fördelning av kompletterande sysslor i samhället. Gandhi ville ge de ´oberörbara´ namnet

Harijan (Guds barn), ett namn som han lånade från en Bhakti helgon från 1700-talet. Hans

avsikt var att inordna dem i Varna systemet som en femte kategori i tron att detta skulle

förändra inställningen hos högkastiga hinduer gentemot de ´oberörbara´. Ambedkar och hans

följeslagare ansåg namnet vara nedvärderande och förkastade det.

Konflikten mellan Ambedkar och Gandhi fick ett politiskt uttryck i deras olika uppfattningar

om de ´oberörbaras´ representation i parlamentet. I samband med överläggningarna i London

1932-1935 om Indien framtida konstitution argumenterade Ambedkar för att de ´oberörbara´

skulle utgöra en fristående väljarkår (separate electorates). Han ville att de ´oberörbara´ skulle

utse sina egna representanter till politiska församlingar. Med denna reform skulle de eftersatta

grupperna bilda en sammanhållen intressegrupp. Gandhi motsatte sig förslaget. Han menade

att det skulle medföra en splittring av den hinduiska samhällsformen. När den brittiska

regeringen gav Ambedkars förslag sitt stöd inledde Gandhi en fasta och hotade att fasta till

döds.

Varför skulle inte de oberörbara säga ”akta er för Gandhi”, skriver Ambedkar, när de vet att

han inte skulle gå med på att använda politiska metoder för att frigöra dem. En människa med

vanligt sunt förnuft, fortsätter han, borde ha förstått att politisk makt i de oberörbaras händer

kunde åstadkomma mer på ett år än en hel orden av predikande munkar kunde åstadkomma

under ett helt sekel. I ett uttalande om Gandhis fasta riktat till Gandhi skrev han:

Jag är övertygad om att många har insett att om det finns någon klass som förtjänar speciella

politiska rättigheter för att skydda sig mot majoritetens tyranni under Swaraj-författningen så

är det de undertryckta klasserna. Här har vi en klass som uppenbarligen inte har möjlighet

att ta vara på sig själva i kampen för tillvaron. Den religion som de är bundna till bereder

dem ingen ärofull plats utan brännmärker dem som spetälska och ovärdiga ett normalt

umgänge. Ekonomiskt är det en klass som är totalt beroende av de högkastiga hinduerna för

sin försörjning

Ambedkar såg sig tvingad att ge med sig och en uppgörelse nåddes (the Poona Pact), som

undertecknades av ledarna för daliterna, inklusive Ambedkar och kongresspartiet. Gandhi,

som ansåg sig stå vid sidan av konflikten undertecknade inte handlingen. Uppgörelsen gav de

´oberörbara´ ett antal reserverade platser i politiska församlingar, som i jämförelse med det

ursprungliga förslaget var en stor förlust för dem.

Detta land som aldrig var vår moder

I boken Detta land som aldrig var vår moder knyts olika berättelser i poesi och bild samman

till en historia om känslan av utanförskap och främlingskap, den omänskliga skändlighet

Daliter lever under. Men de ger också uttryck för reflektion över vari deras osynlighet bottnar,

om uppvaknandet till insikt och om vägen till förändring; att se rebellen inom sig. Jyoti

Lanyewar från Maharashtra beskriver detta i dikten Hål i mitt hjärta, som också gett namn åt

boken:

Deras omänskliga skändlighet har frätt hål

i mitt hjärta av sten.

Jag färdas genom denna skog med försiktiga steg

och blicken fäst vid tidens förändringar.

Borden har vänts upp och ner nu.

Protester pyr

ena stunden här

andra stunden där.

Jag har varit tyst hela denna tid

och lyssnat till talet om rätt och fel.

Men nu ska jag få lågorna att flamma

För mänskliga rättigheter.

Hur kommer det sig att vi hamnat här

i detta land som aldrig var vår moder?

Som aldrig gav oss ens

ett liv som kattor eller hundar?

Jag tar dess oförlåtliga synder som vittnen

och blir här och nu

rebell.

Bildkonstnären Savi Sawarkar föddes 1961 i Nagpur och växte upp i ett område av staden,

som var känt för att vara ett starkt fäste för Ambedkarrörelsen. Ambedkars liv och tankar om

människors lika värde kom därmed tidigt på många sätt att inspirera honom. Sawarkars

farföräldrar hade också långt tidigare anslutit sig till rörelsen. De såg Ambedkar som en

demokratisk statsman med stor intellektuell skärpa och berättade i sagans form om honom för

Savi. Ambedkar hade också valt Nagpur för Daliterna massomvändelse till buddhismen.

Savi Sawarka beskriver drivkraften till sitt sätt att uttrycka sin solidaritet med de ´oberörbara´

så här: Min konst och mina idéer är ett individuellt sätt att nalkas social struktur och religion

i det indiska samhället och jag känner mig utmanad att starta en revolution mot brahminsk

estetik. Jag målar väldigt jordnära ämnen ur vardagslivet, såsom att promenera på en väg i

mörkret och även fotstegen på marken.

Sawarkar fick sin grundläggande utbildning i konstskolor i Indien och i kontakt med

konstnärer i Tyskland, USA och Mexiko kom han att utveckla sin konstform, grafisk

torrnålsteknik. Han kunde liksom andra daliter uppleva och iaktta den diskriminering som

daliterna utsattes för. Hans verkliga styrka var tecknandet. I denna form sökte han uttrycka sitt

inre jag, som var jaget av en dalit och vars ideal var Ambedkar. Oberörbarhet, kast och

brahminskt förtryck var verklighetens teman i samhället och Savi visualiserade detta i sina

bilder. De blir därmed ett uttryck för social kamp, en kamp som har sitt ursprung i arvet efter

Ambedkar.

Hans ikonografiska bilder berättar om existensen som oberörbar i en brahminsk social

ordning som kan ta sin utgångspunkt i en gestalt med spottkrukan hängande runt halsen för att

inte saliven ska orena marken och sopborsten hängande där bak för att sopa bort de egna

fotspåren från marken. Det temat är också ämnet i Arjun Dangles dikt, Revolution, som

beskriver hus de ´oberörbara´ förr i tiden bar krukor om halsen för att hindra deras spott att nå

marken, och kvastar bundna till baken för att sopa bort deras fotspår. Mahar är en oberörbar

grupp i Maharashtra, till vars sysslor hörde att ta hand om döda kreatur. De ropade ”Johar,

ma-bap” (hell dig moder och fader) istället för ”Ram, Ram” eller ”Namaste”. De näst sista

raderna i dikten citerar ironiskt en revolutionär brahminsk poet – de som däremot verkligen

revolterar kastas i elden och förgås.

Savi Sawarkar, Untouchable in pune

Vi brukade vara deras vänner

när vi med lerkrukor hängande runt halsen

och sopkvastar fastsatta vid våra arslen

gick våra rundor i de yttersta gränderna

och ropade: Ma-bap, Johar, Ma.bap.”

Vi slogs med kråkor

och unnade dem inte ens vårt snor

när vi släpade ut yttergrändens döda kreatur,

flådde dem snyggt

och delade köttet mellan oss.

Då på den tiden älskade de oss.

Vi slogs med sjakaler-hundar-gamar-glador

för att vi åt av deras beskärda del.

Idag ser vi en förändring från rot till krona.

Kråkor-sjakaler-hundar-gamar.glador

är våra närmsta vänner.

Yttergrändernas dörrar har stängts för oss.

”Ropa Seger för Revolutionen”

”Ropa Seger”

”Brinn, brinn ni som slår mot traditionen”

Ett tema i Savi Sawarkars bilder är devadasi traditionen inom vilken de lägre kasterna

utnyttjas sexuellt med religiös sanktion från brahminismens religion. Flickor från de

´oberörbara´ familjerna invigdes först i religiösa ritualer till tempelgudinna och därefter i

sexuell normlöshet och prostitution. Ett ordspråk i Maharashtra säger att en devadasi är

bortgift med guden men älskarinna åt hela byn. Familjerna gav sina döttrar ibland som resultat

av religiös tro och ibland för att de tvingades in i systemet genom sin utsatta social ställning.

Savi Sawarkar, Deva-dasi and the husband Goud

I dagens Indien är denna tradition förbjuden anligt lag. Många dalit familjer tvingas ändå

genom ojämlika sociala, kulturella och ekonomiska förhållanden att sälja sina döttrar till

prostitution. En offentlig utfrågning arrangerad av Council for Social Development år 2001 i

delstaterna Karnataka och Tripura avslöjade att genomförandet av lagen, Devadasi System

Abolition Act, hade klara brister och detsamma gällde rehabiliteringen av de kvinnor, som

sluppit loss ur systemet. Luckor i lagen och att offren själva tvekar att klaga medför att

dalitfamiljer av okunnighet och utsatthet fortsatt att tillägna sina döttrar detta system under

tyst medgivande av prästerna.

Hira Bansode, en kvinnliga dalit poet från Poona i Maharashtra, beskriver kvinnans roll i

slavens skepnad

-----

Där storslagna begär lämnas att flyta utför floden

Där hotet från kvinnornas styrka måste jordas

Där lyckan i silvrigt månsken töms i krus av mörker

I det landet är kvinnan ännu slav

Där en kvinna förtvinar i sin ungdom av Tradition är

hon hindrad hela livet som ett förkrympt träd förblir hon

i skuggan av någon annans hus

I det landet är kvinnan ännu slav

I det land där kvinnorna är slavar … påbörjas

ödeläggelsen i tidig timme

Festivalen till herraväldets ära firas grandiost men

berättelserna reciteras med smärta

Att vara född kvinna är orätt

Att vara född kvinna är orätt

Ruth Manorama

En i högsta grad aktiv representant för Daliterna och deras kamp för frigörelse, som i Indien

utgör ca 170 miljoner människor eller tillsammans med övriga länder i och utanför Sydasien

ca 240 miljoner, är Ruth Manorama boende i Bangalore. Hon är en av de tre som tilldelats

utmärkelsen Right Livelihood Award 2006. Priset instiftades år 1980 av Jakob von Uxekull

och tilldelas dem som visar på nya idéer och möjligheter att förändra orättfärdiga sociala

system. Visionen bakom priset är att föra samman människor från olika delas av världen som

verkar för avspänning och fred, mänskliga rättigheter och social rättvisa, miljöhänsyn och

förnyelsebar utveckling och vetenskapliga landvinningar inriktade på mänskliga behov.

Click for high resolution picture <br>(free to use)

Ruth Manorama

India

Right Livelihood Award 2006

"...for her commitment over

decades to achieving equality

for Dalit women, building

effective and committed

women's organisations and

working for their rights at

national and international

levels."

I juryns motivering för priset presenteras Ruth Manorama som den indiska halvöns mest

effektiva organisatör och talesman för Dalit kvinnor. Juryn hedrar Ruth Manorama, som själv

är Dalit ”för hennes livslånga engagemang att uppnå jämlikhet för Dalit kvinnor, skapa

effektiva kvinnoorganisationer och arbeta för kvinnors rättigheter på nationell och

internationell nivå”.

I februari i år följde jag Ruth Manorama till Chennai, där hon och hennes organisation, som så

många andra, är delaktig i återuppbyggnaden av hus och fiskenäringen som spolades bort av

tsunamin. De förmedlade medel till ett par nya båtar och för reparation av bostadshus i ett

område strax utanför staden. Då, i februari, ett år efter katastrofen var det svårt att direkt se

vidden av vad som hänt. Man pekade på den breda strandremsan, ”där på stranden spelade ett

tjugotal ungdomar cricket, havet tog dem alla, de bara försvann”.

Förluster av det slaget skapar nya frustrationer. Men det fanns mer än så av konflikter i denna

samfällighet, kastgrupper och religiösa grupper vars ställning gentemot varandra inte sällan

leder till våldsamheter. Det är här jag återigen ser Ruth Manoramas mänskliga auktoritet i

förmågan att möta människor och förmedla vägen till att överbrygga sociala och kulturella

motsättningar och att se varandra som människor med gemensamma önskningar och behov.

Det är en början till försoning.

Män och kvinnor samlas först i områdets kyrka. Vi sitter på golvet längs väggarna, kvinnor

och män på var sin sida. Språket är tamil och jag förstår inte orden. Men jag förstår den

absoluta tystnaden, koncentrationen och blickarna som är fästa på Ruth, som talar sakta men

med ett eftertryck som ger resonans. Efteråt samlar hon männen kring sig för att tala om

ledarskap och förmågan att se varandra som människor med lika behov och önskningar och

om framsteg genom samarbete. Vi sitter i den varma sanden invid havet, där nattens mörker

sluter sig tätare kring oss och tidvattnet klättrar allt närmare. Då det är hotfullt nära fortsätter

vi mötet på den närbelägna parkeringsplatsen.

Ruth menar att även om förändring av Daliternas villkor är en prioriterad fråga kan detta inte

förverkligas om man inte kan nå ömsesidig respekt mellan människor. Förbättrade villkor för

en samhällsgrupp får inte ske på bekostnad av en annan. Förståelse, tolerans och samexistens

är återkommande tema i hennes tal och praktiska gärning på fältet.

Ruth Manorama har i praktiken följt Ambedkars uppmaning att utbilda, agitera och organisera

för att nå resultat:

… to get education as much as possible for gaining knowledge and wisdom;

to organize themselves for being a strong force to reckon with;

to agitate for achieving the constitutional rights as well as human rights;

to endeavour for the establishment of a society based on freedom, equality and fraternity

(Ambedkar, Code of Conduct)

Foto: Kalhander Basha, Ruth Manorama

Ruth Manorama betonar att Dalit-kvinnornas villkor i Indien måste uppmärksammas. De är

en av de till antalet största socialt segregerade grupperna i världen och utgör drygt 16 % av

det totala antalet kvinnor i landet. Dalit kvinnor är trefaldigt diskriminerade efter klass, genus

och kast: de är fattiga, de är kvinnor och de är Daliter. De är diskriminerade inte bara av de

högkastiga utan också inom den egna samhällsgruppen, där männen dominerar. Kvinnor är

aktiva i Dalitrörelsen men har få ledande positioner.

Ruth Manorama menar att den indiska regeringen har en skyldighet att leva upp till de lagar

och FN-konventioner man antagit för att främja kvinnors fri- och rätigheter i allmänhet och

Dalit kvinnors i synnerhet. Det gäller rätten till liv, frihet från tortyr eller omänsklig

behandling, rätt till likhet inför lagen, till ett privat skyddat liv, rättenn ingå äktenskap av fri

vilja, och rätten at vara fullt delaktig i offentliga ärenden. Hon pekar också på barnens

utsatthet. I Indien är 46 % av barnen inte registrerade vid födseln, inte heller finns ett

fungerande system för registrering av äktenskap. Detta försvårar möjligheten att skydda Dalit

flickor från sexuell exploatering och trafficking, barnarbete och påtvingade tidiga äktenskap.

De lagar som finns till skydd för kvinnor iakttas i påfallande begränsad utsträckning. Likaså

brister regeringen och delstatsregeringarna i att förverkliga en acceptabel levnadsstandard för

den fattiga delen av invånarna, där majoriteten av daliterna ingår. Det gäller bostad,

utbildning, hälsovård, arbetsmöjligheter, säkerhet i arbetsmiljön.

Dalit kvinnor är utsatta för olika former av våld, som ofta får passera utan påföljd för

förövaren. Det kan gälla verbalt nedvärderande ofta sexuella tillmälen, att bli tvingad paradera

naken eller att dricka urin eller mord efter anklagelse on häxeri, hot om eller verkliga

våldtäkter. Tempelprostitution, Devadasi, förekommer trots förbud i lag sedan många år.

Huvuddelen av våldet mot kvinnor registreras ofta inte och även när så sker visar polisen och

rättssystemet begränsat intresse att fullgöra sina åtaganden enligt lag.

Kvinnor har samtidigt varit aktiva deltagare i olika för Indien viktiga händelser, till exempel i

anti-kast rörelsen under 1920-talet och i frihetsrörelsen mot det brittiska kolonialväldet. De är

likaså ofta bärare av kampen för daliters rättigheter, till exempel för rätten till landrättigheter i

tusentals byar och intar många platser i by råden, Panchayati Raj, efter reformen som kvoterar

en tredjedel av platserna till kvinnor. Faktum är ändå att detta inte förhindrar det strukturellt

betingade våldet och diskrimineringen av dem. Våld i kombination med straffrihet fortsätter

att hålla dem kvar i en andra rangens plats.

Sedan 1980-talet har Dalit kvinnor därför sett behovet av en egen plattform, skapad och

kontrollerad av dem själva, genom vilken de kan föra kampen för fri- och rättigheter för dem

själva men också för daliterna som helhet, män som kvinnor. Initiativtagarna till en sådan

plattform betonar att detta inte ska ses som en splittring. De försäkrar istället att de klart ser

behovet att bygga en stark allians mellan Dalitrörelsen, kvinnorörelsen och den rörelse

Dalitkvinnorna formerat.

Ruth Manorama har varit med som initiativtagare till alla dessa tre rörelser, National Alliance

for Women, National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights och National Federation of Dalit

Women.

------------------

THE NAXALITE MOVEMENT 2012-06-20

India Political Map

Hans Magnusson; Dalit Solidarity Network-Sweden; Den här e-postadressen skyddas mot spambots. Du måste tillåta JavaScript för att se den.

The Naxalite Movement

Mapping the Naxalites

Click any State on the map and get the Detailed State Map

Source: http://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/india/india-political-map.htm

The Naxalite Movement – since September 2004 united under one banner, Communist Party

of India (Maoist) – has since its formal start in 1967, despite internal splits and

reorganizations, succeeded in spreading its ideology and their physical occupation of large

parts of rural territories of India. Particularly notable, as C. W. Punther1 (2010) points out, is

their achievement to establish liberated zones over vast amounts of land, over which the

Naxalites wield uncontested control through a combination of political mobilization and

coercion. . At present, Naxalites have a presence in almost half of India's 28 states. Raju J.

Das2 (2011) visualizes its progress with his statement that since its foundation the Naxalite

movement has grown from being a ´local flare-up´ organization to a regional movement,

having its presence to some degree of intensity in a quarter of India´s 600 districts, thus

covering 40 % of the country´s geographical area. In the regions where the Naxalite presence

has been established for decades many people see the Naxalite leadership as the sole source

of authority.

1 C. W. Punter 2010: 27; The Naxalite Movement in India from Independence-Present: Theoretical and

Pragmatic; Challenges of Counterinsurgency within the Framework of a Constitutional Democracy. Cody

referring to John Mackinlay (2010) The Insurgent Archipelago and Haringer Signh (2010) Counting the Naxals;

Institute for Defense Studies.

Bidyut Chakrabarby and Rajat Kumar Kujur (2010) remarks that although the Nepali Maoists “have abdicated

the path of violent revolution by joining the government, it would not be wrong” to include the mentioned part

of Nepal.

2 Raju J. Das 2011: 281, Radial Peasant Movements and Rural Distress in India; in W- Ahmed, A. Kundu, and R.

Peet, ed. India´s New Economic Policy; A Critical Analysis ,Routledge (2011), New York

3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File: India_Red_Corridor_map.png

4 Bidyut Chakrabarby and Rajat Kumar Kujur (2010: 27), Maoism in India, Reincarnation of ultra-left wing

extremism in the twenty-first century, Routledge, New York

5 Punter (2010), ref. to Singh, Harinder, Countering the Naxals; Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. June

11, 2010

6 http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/150859/Dandakaranya

The Naxalites have mapped a Red Corridor3 stretching from Nepal to Tamil Nadu, thus

linking a significant part of the subcontinent. It covers a vast land mass stretching from

Pashupati in Nepal to Tirupati in Tamil Nadu and runs through a compact geographical zone

involving 13 states, including from north to south the states of Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh,

Bihar, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Orissa, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Andhra

Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala4. The Red Corridor extends over areas that are

the most impoverished regions in modern India and thus the areas where people suffer from

the greatest illiteracy, poverty and overpopulation.

As of June 2010, the Naxalites were able to claim a total of 72,000 square kilometers as

being unquestionably under their political and military control5. This area included

Dantewada, Bastar, Bijapur and Narayanpur in Chhattisgarh; Malkinigiri and Rayagada in

Orissa; West and East Singhbhum in Bihar; Gadchiroli in Maharashtra; and West Midnapore

in West Bengal. A large part of this area is the Dandakaranya region or Dandakaranya Forest6

The "Red-Corridor" by Mritunjay

http://www.countercurrents.org/desai110510.htm Arundhati Roy (2010: 9), Walking with the Comrades,

OUTLOOK INDIA March 21, 2010

in east-central India. Extending over an area of about 40,000 square kilometers it includes

the Abujhmar Hills in the west and borders the Eastern Ghats in the east. It has dimensions

of about 320 km from north to south and about 480 km from east to west.

The Red Corridor

Map: Uploaded by Mritunjay October 8, 2009 http://www.nowpublic.com/world/red-corridor-0

What the Maoists term as the Dandakaranya Special Zone7 is the vast forest area situated

between the borders of four states – Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra and Orissa.

The Maoists have five organizational divisions – the south, west and north Bastar divisions,

the Maad and Gadchiroli divisions – covering the entire area. It is this area where the

Maoists have formed their own people´s government, Jantanam Sarkar (JS).

7 Mike Ely (2008), Dandakaranya – Two Paths of Development in India

http://kasamaproject.org/2008/01/23/awtw-dandakaranya-india-%E2%80%93-two-paths-of-development/

8 C. W. Punter 2010: 28

9 Basudev 2007: 3 ff; Naxal Movement in India: Peoples' Struggle transformed into a Power Struggle, Nov 11

2007 http://orissanewsfeatures.sulekha.com/blog/post/2007/11/naxal-movement-in-india-peoples-struggle-

transformed.htm

10 Basudev 2007: 4, Naxal Movement in India: Peoples' Struggle transformed into a Power Struggle,

http://orissanewsfeatures.sulekha.com/blog/post/2007/11/naxal-movement-in-india-peoples-struggle-

transformed.htm

The Dandakaranya region holds mineral rich forest land and the Indian government has

launched a military operation to drive out the Naxalites so that Indian and multinational

corporations can exploit the iron ore, coal and bauxite resources.

The Naxalite groups have further established a network with ideologically similar

organizations in Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. A turning point in this respect was

the convening of the Coordination Committee of Maoist parties and Organizations of South

Asia (CCOMPOSA), where Maoist groups across South Asia reaffirmed their dedication to

armed struggle8. Additionally, these South Asian Maoist organizations and parties are

members of an international organization called the Revolutionary Internationalist

Movement (RIM)9.

The 2006 US State Department’s Country Report on Terrorism, drawing on media reports

and local authorities, estimates the membership of the CPI's (Maoist) to be as high as

31,000, including both hard-core militants and dedicated sympathizers. According to the

report women constitutes a significant part of the CPI (Maoist) cadre. However, the report

also states that it is difficult to assess its strength with any accuracy and Basudev10 (2007)

means that the number would have gone up considerably by now, as entry into the fold is a

regular process in the cadre groups.

The Naxalite Movement – a radical social movement

or a menace to society

How should one perceive the Naxalite movement? Is it a radical social movement involved in

a consistent struggle, also armed struggle, for the benefit of the poor and exploited people,

deliberately isolated and marginalized by the Indian Government, or is it to be viewed as

menace to the society as a whole? Depending on which side of the ideological and socio-

political fence dividing the Indian society people are two different positions are voiced.

Viewing the emergence of protest movements in a broader perspective, Raju D. Das´s11

points out that peasants have often been important protagonists in the class struggles

occurring in newer post-colonial societies, in Asia as well as in Latin America. In India, he

asserts, the Naxalite movement, so called because it started in the Naxalbari region of the

West Bengal province, is one such peasant struggle. Its continued existence “is a window on

an Indian countryside in perpetual development distress” ... and this distress … “has only

been worsened by the neoliberal New Economic Policy emphasizing ´free´ markets,

legitimizing the state´s withdrawal from pro-poor and pro-peasants activities, and

advocating free export and import of commodities, including farm products.” Raju D. Das

thus relates the emergence and the continuance of the Naxalite movement to the basic

failure of capitalist development and the failure of the post-colonial state to bring significant

benefits to the broad mass of the population, a state of affairs that has sharpened under

neoliberalism because capital becomes increasingly more exploitative, and additionally, the

state is increasingly withdrawing from the provision of welfare to the masses. Hence,

according to Das, the Naxalite movement in terms of its original occurrence, and its

continual existence must be explained in terms of multiple causes; class exploitation and

social oppression, the state´s development failure, and the success of the Naxalite

movement as a development factor. And, Punter12 fills in – “… it must be acknowledged

therefore, that in failing to deal with the underlying causes of tribal disaffection, the state

has effectively allowed for a rival political and socio-economic form of governance to

establish its authority in certain regions of the country.”

11 Raju J. Das 2011: 281, Radical Peasant Movements and Rural Distress in India; in W. Ahmed, A. Kundu, and R.

Peet, ed. India´s New Economic Policy; A Critical Analysis ,Routledge, 2011, New York

12 Punter (2010: 27), ref to Mackinlay, John, The Insurgent Archipelago (2010:18)

13 Arindam Chaudhuri, Long will live the Naxalite movement, (The exact date of this article is not known...);

http://naxalrevolution.blogspot.com/2009/01/indias-crony-capitalism-which-is.html

Arindam Chaudhuri13 underlines this analysis, saying that the Naxalites “are the only

revolutionary group in this country at the centre of whose agenda are the poor and

deprived. Their methods may involve violence, but then worldwide, all uprisings and

revolutions have been violent. To the people against whom they fight, they are villains –

terrorists if you may call them – but the people for whom they fight, they are the heroes.”

The 2007 federal budget, taken as an example by Chaudhuri, reveals how the state, over

successive governments, prioritizes its development policy. In this budget the government

allocated Rs 90,000 crore for establishing Special Economic Zones (or ‘land loot schemes’ in

Chaudhuri´s words). Another Rs 2, 35,000 crore of subsidies went into the corporate cash

box. This, Chaudhuri argues, is part of the government´s economic industrial policy in

helping a few industrial houses to acquire more and more land and public property …

“villages are being emptied; people are being uprooted and displaced and their mineral and

iron-ore rich lands left behind being handed over to the Tatas and Mittals.” Chaudhuri

compares the amount subsidizing corporate capital with that being allocated for

unemployment eradication programmes, which were to guarantee at least ‘100 days job’ per

person; “against a most urgent requirement of about Rs 2,25,000 crore, the allocation is a

meager Rs 11,000 crore.” So, he reasons, “If the poor in a country are left to die out of

hunger, curable diseases and poverty, Naxalites will rule. The only way to defeat them is for

our governments to believe in fact in what the Naxalites are fighting for – food, health and

employment. Till our governments allocate enough for such causes, many more

Chhattisgarh14 carnages will happen; and unfortunately, I won’t be able to blame the

Naxalites, or even call them terrorists.”

14 “On 6 April, Naxalite rebels killed 76, consisting of 74 paramilitary personnel of the CPRF and two policemen.

Fifty others were wounded in the series of attacks on security convoys in Dantewada district in the central

Indian state of Chhattisgarh (BBC World. 6 April 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8604256.stm.

The attack resulted in the biggest loss of life security forces have suffered since launching a large-scale

offensive against the rebels.”

15 In Conversation with Ganapathy, General Secretary of CPI (Maoist) in an interview with Jan Myrdal and

Gautam Navlakha, January 2010

The General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), Muppala Lakshmana Rao

alias Ganapathy15, describes the role of the party and its military wing, the People’s

Liberation Guerrilla Army, in these words:

“Hence, at the present juncture our Party can play a significant role in rallying all

revolutionary, democratic, progressive and patriotic forces and people. Because our party

has an all India character, good political militant mass base in several States, a People’s

Liberation guerrilla Army fighting the enemy in several States and emerging New Democratic

People’s power in Dandakaranya, Jharkhand and some other parts of India. We have a

clear.cut understanding to unify all revolutionary, democratic, progressive, patriotic forces

and all oppressed social communities including oppressed nationalities against imperialism,

feudalism and comprador bureaucratic capitalism. Our New Democratic United Front

consists of four democratic classes, i.e. workers, peasants, urban petty.bourgeoisie and

national bourgeoisie. If we wish to form a strong United Front then it must be under

leadership of the proletariat, basing on worker and peasant alliance. If we wish to form a

strong United Front then it must be supported and defended by the People’s Army. Without

People’s Army people have nothing to achieve or to defend. Hence enemy is seriously trying

to eliminate our Party leadership with the aim of destroying a revolutionary and democratic

centre of Indian people. So the condition has matured further to rally around one centre and

revolution could go ahead under the leadership of the Communist Party of India (Maoist).”

He also says that the Dandakaranya Jantanam Sarkars (people´s government) of today are

the basis for the Indian People’s Democratic Federal Republic of tomorrow16.

16 The Dandakaranya Janathana Circars of today Message sent by Comrade Ganapathy.

Message sent by Comrade Ganapathy on behalf of Politbureau to the magazine of Dandakaranya Janathana

Circar. PEOPLE’S MARCH Voice of the Indian Revolution Vol.11 No. 1, Jan.Feb. 2010 p. 22.26 and 13, 18

17 Bidyut Chakrabarty and Rajat Kumar Kujur (2010: 10), Maoism in India; Reincarnation of ultra-left wing